A Breath of Bronze and Stone: A History of Ancient Greece

Table of Contents

- Prologue: Echoes in the Marble: Introduces the enduring presence of Ancient Greece in modern life, setting the stage for the historical narrative. Dr. Theron reflects on her personal connection to the subject, emphasizing the importance of understanding the past to navigate the present. The chapter ends with a question: What can we learn from the Greeks?

- The Bronze Age Dawn: Minoans and Mycenaeans: Explores the pre-Classical civilizations of Crete and mainland Greece, highlighting their cultural achievements and laying the groundwork for later developments. A comparison of the two cultures and how their collapse set the stage for the rise of the Greek city-states.

- The Dark Ages and the Rise of the Polis: Examines the period of upheaval and transition following the collapse of the Mycenaean civilization, tracing the emergence of the independent city-states (poleis). This chapter details the evolution of their political structures and social organizations.

- Homer and the Shaping of the Greek Identity: Explores the impact of the Iliad and the Odyssey on Greek culture, examining how these epic poems shaped their values, beliefs, and sense of identity. An analysis of the characters and themes present in the epics.

- Sparta: Discipline and the Art of War: Focuses on the unique society and military culture of Sparta, exploring its rigid social hierarchy, its emphasis on discipline, and its role in Greek politics. A look into the Spartan military system, their training, and their societal impact.

- Athens: The Birthplace of Democracy: Delves into the evolution of Athenian democracy, from its early origins to its golden age under Pericles. A detailed examination of the Athenian political system, its strengths, and its weaknesses.

- The Persian Wars: A Clash of Civilizations: Narrates the epic struggle between Greece and the Persian Empire, highlighting the key battles and the heroic resistance of the Greek city-states. An analysis of the strategic decisions made by both sides and their consequences.

- The Golden Age of Athens: Art, Philosophy, and Drama: Celebrates the cultural and intellectual achievements of Athens during the 5th century BC, examining its iconic architecture, its philosophical innovations, and its dramatic traditions. A spotlight on the works of famous playwrights, sculptors, and philosophers.

- The Peloponnesian War: The Fall of an Empire: Explores the devastating conflict between Athens and Sparta, tracing its origins, its key events, and its far-reaching consequences. An examination of the political and social tensions that led to the war, and the strategies employed by both sides.

- Socrates and the Search for Truth: Focuses on the life and teachings of Socrates, examining his method of inquiry, his ethical principles, and his tragic fate. An analysis of his philosophical contributions and his impact on Western thought.

- Plato and the Ideal State: Delves into the philosophy of Plato, exploring his theory of Forms, his concept of the ideal state, and his influence on Western political thought. A discussion of his dialogues and his attempts to define justice and virtue.

- Aristotle: Logic, Science, and Ethics: Explores the wide-ranging contributions of Aristotle to logic, science, and ethics, examining his method of observation and analysis, his classification of knowledge, and his concept of virtue. A look at his influence on various fields of study.

- Alexander the Great: Conquest and Hellenism: Narrates the conquests of Alexander the Great, tracing his rise to power, his military campaigns, and his creation of a vast empire that spread Greek culture throughout the Eastern Mediterranean. An analysis of his legacy and the spread of Hellenistic culture.

- The Hellenistic World: A Fusion of Cultures: Examines the cultural and political landscape of the Hellenistic period, exploring the fusion of Greek and Eastern traditions, the rise of new kingdoms, and the flourishing of art and science. A look at the major Hellenistic cities and their contributions to art, science, and philosophy.

- The Legacy of Greece: Enduring Influence: Explores the enduring influence of Ancient Greece on Western civilization, examining its contributions to art, literature, philosophy, politics, and science. A discussion of how Greek ideas and values continue to shape our world.

- Epilogue: A Timeless Echo: Concludes with a reflection on the lessons that can be learned from Ancient Greece, emphasizing the importance of democracy, reason, and humanism. Dr. Theron shares her final thoughts on the enduring legacy of the Greeks.

Prologue: Echoes in the Marble

The scent of rain-soaked marble hangs heavy in the air, a fragrance as familiar to me as the taste of olives or the sound of bouzouki music drifting from a taverna on a summer evening. Here, standing amidst the crumbling columns of the Ancient Agora in Athens, I feel the past not as a distant echo, but as a palpable presence, a breath of bronze and stone that still whispers on the wind.

These stones, worn smooth by the passage of millennia, have witnessed the birth of democracy, the philosophical inquiries of Socrates, the triumphs and tragedies of a civilization that, despite its temporal distance, continues to shape our world in profound and often unseen ways. We walk on streets laid out by their hands, speak languages shaped by their tongues, and grapple with philosophical questions they first articulated.

My own connection to this past is, perhaps, more intimate than most. Growing up in the shadow of the Acropolis, I absorbed the stories of ancient Greece with my mother's milk. My father, a scholar of the Peloponnesian War, filled our home with the strategic brilliance of Pericles and the tragic downfall of Alcibiades. My mother, a linguist, revealed the subtle nuances of the ancient Greek language, unlocking the secrets hidden within Homer's epic poems and Plato's philosophical dialogues.

But it was not merely the academic environment that fostered my passion. It was the tangible reality of ancient Greece that surrounded me, the weight of history pressing down from every crumbling wall, every fragmented vase shard unearthed in our garden. I remember, as a child, tracing the inscriptions on ancient tombstones, feeling the rough texture of the marble beneath my fingertips, and imagining the lives of those who had walked these streets before me.

This book, then, is not simply a chronological recounting of events. It is an attempt to breathe life back into the past, to understand the ancient Greeks not as remote figures frozen in time, but as complex, flawed, and ultimately human beings whose struggles and triumphs continue to resonate across the centuries. It is a journey through their world, a world of vibrant city-states, bustling marketplaces, and soaring temples dedicated to capricious gods.

We will explore the origins of their civilization, tracing the rise and fall of the Minoan and Mycenaean cultures that laid the groundwork for later developments. We will witness the birth of the polis, the independent city-state that became the defining political unit of ancient Greece. We will delve into the world of Homer, examining the Iliad and the Odyssey and exploring how these epic poems shaped the Greek identity and instilled enduring values.

We will confront the stark contrasts between Sparta, with its rigid social hierarchy and its relentless focus on military discipline, and Athens, the birthplace of democracy, a society that celebrated individual liberty and fostered intellectual and artistic innovation. We will examine the evolution of Athenian democracy, celebrating its revolutionary ideals while acknowledging its limitations, particularly regarding slavery and the exclusion of women.

The Peloponnesian War, a pivotal conflict that reshaped the Greek landscape, will be examined in detail, highlighting the strategic brilliance of figures like Pericles and the devastating consequences of hubris and internal strife. We will also delve into the rich tapestry of Greek mythology and religion, revealing how these beliefs influenced art, literature, and social customs. The stories of gods and heroes, from Zeus on Mount Olympus to Heracles and his impossible labors, are not mere fables, but reflections of the Greek worldview, their anxieties, and their aspirations.

Beyond the battlefield and the political arena, we will explore the intellectual ferment of ancient Greece, showcasing the groundbreaking contributions of philosophers like Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, whose ideas continue to resonate in contemporary thought. We will examine the artistic achievements of the Greeks, from the iconic architecture of the Parthenon to the expressive sculptures that captured the human form with unparalleled realism.

But more than just the grand narratives of emperors and philosophers, I want to tell you the stories of the everyday citizens. The farmers tilling the rocky soil, the merchants haggling in the agora, the women weaving tapestries in their homes, the slaves toiling in the silver mines. Their lives, too, are a vital part of this story, a tapestry woven from threads of hardship, resilience, and quiet dignity.

I often reflect on my own journey as a historian. It’s a path paved not only with academic papers and dusty archives, but also with personal moments of revelation. One such moment occurred during an archaeological dig on the island of Crete. We were excavating a Minoan palace when we unearthed a small, clay tablet inscribed with Linear A script. As I carefully brushed away the centuries of accumulated dirt, I felt a surge of connection to the person who had held that tablet in their hands, thousands of years ago. It was a humbling reminder that history is not an abstract concept, but a living, breathing reality, a story written in the stones and artifacts that we unearth.

And it is a story that continues to unfold. The echoes of ancient Greece reverberate in our modern world, shaping our institutions, our values, and our very understanding of ourselves. From the foundations of democracy to the principles of rational thought, the legacy of the Greeks is undeniable.

But what, ultimately, can we learn from the Greeks? What lessons can we draw from their triumphs and their failures? How can their experience inform our understanding of the challenges we face today?

These are the questions that will guide us on our journey through the world of ancient Greece.

And as we begin to explore this breath of bronze and stone, I believe we will discover not only a deeper understanding of the past, but also a clearer vision of our own future. The past is never truly gone. It lingers, a silent advisor.

But a shadow falls over the knowledge now. What good is the past when war is on the horizon? The earth trembles beneath our feet, not from an earthquake, but from the coming storm.

What can we learn from the Greeks, indeed? Perhaps, we are about to find out.

The Abandoned City

The Rise of the Polis

Chapter 2: The Bronze Age Dawn: Minoans and Mycenaeans

The Aegean Sea, a cradle of civilizations, holds secrets whispered on the salt-laced winds. Before the Parthenon stood sentinel above Athens, before the Spartan phalanx marched to war, another world flourished: the Bronze Age Aegean. This chapter will delve into the pre-Classical societies of Crete and mainland Greece, the Minoans and Mycenaeans, exploring their cultural achievements, their unique societal structures, and ultimately, their enigmatic collapses that paved the way for the rise of the Greek city-states. We must remember, though, that our understanding of these cultures is necessarily incomplete, pieced together from archaeological fragments and tantalizing, often undeciphered, textual clues. We are, in essence, trying to reconstruct a shattered vase, knowing that some shards are forever lost.

The Minoans, centered on the island of Crete, were the first to leave a significant mark on the Aegean landscape. Beginning around 2700 BCE, they developed a sophisticated palace culture, characterized by complex administrative systems, elaborate artistic traditions, and a seemingly peaceful, maritime-oriented society. Their palaces, such as Knossos, were not merely royal residences, but also served as centers of economic activity, religious ritual, and artistic production. Imagine, if you will, the bustling courtyards filled with merchants haggling over goods from distant lands, the rhythmic clang of bronze workers forging weapons and tools, and the vibrant frescoes adorning the walls, depicting scenes of bull-leaping, religious processions, and the natural beauty of the Cretan landscape.

The frescoes themselves offer a glimpse into the Minoan psyche. Unlike the later, more martial-minded Mycenaeans, the Minoans seemed to celebrate life and nature. Their art is filled with images of dolphins, lilies, and graceful human figures engaged in joyful activities. This has led some scholars to posit that Minoan society was matriarchal or at least afforded women a higher status than was typical in later Greek societies. While definitive proof remains elusive, the prominence of female figures in Minoan religious iconography and the depictions of women participating in public ceremonies certainly suggest a more egalitarian social structure than that of their mainland counterparts.

The Minoans developed a unique writing system, known as Linear A, which remains undeciphered to this day. The inability to read Linear A is a constant frustration for historians, as it prevents us from fully understanding Minoan political organization, religious beliefs, and social customs. However, the very existence of Linear A demonstrates the sophistication of Minoan administration and their need to keep detailed records of economic transactions and other important events. This alone suggests a highly organized and centralized state, capable of managing a complex network of trade and commerce.

Their maritime prowess allowed them to establish trade routes throughout the Aegean and beyond, connecting them with Egypt, the Near East, and other parts of the Mediterranean world. They exported Cretan goods, such as pottery, textiles, and olive oil, and imported raw materials, such as copper, tin, and ivory. This exchange of goods and ideas undoubtedly influenced Minoan culture, exposing them to new technologies, artistic styles, and religious beliefs.

Around 1450 BCE, a cataclysmic event struck Crete. Archaeological evidence suggests that a massive volcanic eruption on the island of Thera (modern-day Santorini) triggered a tsunami that devastated Minoan coastal settlements. The eruption also likely caused widespread environmental damage, disrupting agricultural production and leading to economic instability. While the eruption of Thera certainly contributed to the decline of Minoan civilization, it was not the sole cause. Archaeological evidence also suggests that the Mycenaeans, who had been gradually increasing their influence in the Aegean, seized the opportunity to conquer Crete and establish their own rule.

The Mycenaeans, based in mainland Greece, were a warrior culture, characterized by fortified citadels, elaborate burial rituals, and a more hierarchical social structure than that of the Minoans. Their citadels, such as Mycenae and Tiryns, were built on strategic hilltops, surrounded by massive walls constructed of cyclopean masonry – so called because later Greeks believed that only giants could have lifted such enormous stones. These fortifications reflect the turbulent political landscape of the Mycenaean world, where rival kingdoms constantly vied for power and resources.

Unlike the seemingly peaceful Minoans, the Mycenaeans were obsessed with warfare and hunting. Their art is filled with images of warriors, chariots, and scenes of battle. The discovery of numerous weapons and armor in Mycenaean tombs further underscores their martial culture. The shaft graves at Mycenae, excavated by Heinrich Schliemann in the late 19th century, yielded a treasure trove of artifacts, including gold masks, daggers inlaid with precious metals, and elaborate jewelry. These finds provided tangible evidence of the wealth and power of the Mycenaean elite, as well as their sophisticated artistic skills.

The Mycenaeans adopted the Minoan writing system, adapting it to their own language and creating Linear B. Unlike Linear A, Linear B was deciphered in the 1950s by Michael Ventris, revealing that the Mycenaeans spoke an early form of Greek. The decipherment of Linear B provided invaluable insights into Mycenaean society, confirming their hierarchical social structure, their dependence on agriculture, and their complex administrative system. The Linear B tablets, mostly found in palace archives, provide a glimpse into the daily lives of the Mycenaeans, revealing details about their economic activities, religious practices, and social organization.

The differences between the Minoans and Mycenaeans are significant. The Minoans, a maritime civilization centered on Crete, seem to have prioritized trade, art, and a more egalitarian social structure. The Mycenaeans, based on the mainland, were a warrior culture, focused on conquest, defense, and a hierarchical society. Yet, despite these differences, the two cultures were intertwined, with the Mycenaeans borrowing heavily from Minoan art, architecture, and writing. The Mycenaean conquest of Crete marked a turning point in Aegean history, as the Mycenaeans became the dominant power in the region.

Around 1200 BCE, the Mycenaean civilization began to decline. The causes of this decline are complex and still debated by historians. Some scholars attribute it to internal factors, such as overpopulation, environmental degradation, and social unrest. Others point to external factors, such as invasions by foreign peoples, possibly the mysterious "Sea Peoples" mentioned in Egyptian records. Whatever the causes, the collapse of the Mycenaean civilization ushered in a period of upheaval and transition known as the Greek Dark Ages.

The collapse of the Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations had profound consequences for the future of Greece. The destruction of the palace centers led to a decentralization of power and a decline in literacy and artistic production. However, the Dark Ages were not simply a period of decline. They were also a time of innovation and transformation, as new social structures and political institutions began to emerge. The independent city-states (poleis) that would come to define Classical Greece began to take shape during this period, laying the groundwork for the rise of Athenian democracy and Spartan militarism. The cultural memory of the Bronze Age, preserved in myths and legends, would continue to influence Greek art, literature, and religion for centuries to come.

The fall of these Bronze Age societies provides a stark reminder of the fragility of even the most advanced civilizations. Environmental disasters, internal strife, and external threats can all contribute to the collapse of empires. The lessons of the Minoans and Mycenaeans are particularly relevant in our own time, as we face similar challenges of climate change, social inequality, and geopolitical instability. As we move into the study of the Dark Ages and the rise of the Polis, we will examine how the seeds of those later Greek societies were sown in the fertile, albeit tumultuous, ground left behind by their Bronze Age predecessors. But were the seeds of the collapse sown earlier, in the very structures of their societies? The next chapter will begin to explore this intriguing question.

Minoan Palace of Knossos

Mycenaean Warrior's Grave

Chapter 3: The Dark Ages and the Rise of the Polis

The collapse of the Mycenaean world around 1100 BCE marks a period in Greek history often shrouded in shadows – a time of upheaval and transition that we conventionally, perhaps somewhat melodramatically, term the "Dark Ages." It’s a label that speaks more to our limited understanding than to a factual assessment of unremitting gloom. While archaeological evidence does point to a decline in material culture, literacy, and population, it is crucial to remember that a lack of written records doesn't equate to a complete absence of societal development. Indeed, within this apparent darkness, the seeds of the Classical Greek civilization were quietly germinating, most notably in the emergence of the polis, the independent city-state that would become the defining characteristic of the Greek world.

The reasons for the Mycenaean collapse are complex and likely multifaceted. The eruption of Thera, which we discussed in the previous chapter, certainly played a role, weakening Minoan civilization and making it vulnerable to Mycenaean expansion. Internal strife, overpopulation, and climate change may have also contributed to the decline. However, the most widely accepted theory points to the arrival of the Dorians, a Greek-speaking people from the north, who migrated southward, possibly driven by environmental pressures or resource scarcity.

The Dorians, though often depicted as barbaric invaders, likely integrated into the existing population over time, contributing to the gradual transformation of Mycenaean society. This period saw a significant shift in social and political structures. The centralized palace system of the Mycenaeans gave way to a more decentralized system of independent communities, each centered around a fortified settlement. These settlements, initially small and relatively insignificant, gradually evolved into the poleis, the self-governing city-states that would shape the course of Greek history.

The transition from the Mycenaean era to the rise of the polis was a slow and uneven process, spanning several centuries. During this time, Greece experienced a decline in trade, a loss of artistic skills, and a simplification of social structures. Writing largely disappeared, and knowledge was transmitted orally through stories, songs, and legends. It is in this period that the oral traditions of Homer took shape, preserving fragments of the Mycenaean past and shaping the cultural identity of the emerging Greek world. The Iliad and the Odyssey, while set in the Bronze Age, reflect the social and political values of the Dark Ages, offering glimpses into the lives of warriors, farmers, and kings.

The polis was more than just a geographical entity; it was a community of citizens who shared a common identity, a common culture, and a common set of values. It was a self-governing political unit, responsible for its own defense, its own laws, and its own economic well-being. The rise of the polis was a revolutionary development in human history, marking a departure from the centralized empires of the Near East and paving the way for the development of democracy and individual liberty.

The political structures of the early poleis varied considerably. Some were ruled by kings (monarchies), others by small groups of aristocrats (oligarchies), and still others by tyrants who seized power through force or popular support. However, over time, many poleis gradually evolved towards more democratic forms of government, where citizens had the right to participate in decision-making.

One of the key factors that contributed to the rise of the polis was the development of the hoplite phalanx, a new form of military organization that emphasized the importance of citizen soldiers. Hoplites were heavily armed infantrymen who fought in close formation, relying on their discipline and teamwork to overcome their enemies. The hoplite phalanx required a high degree of social cohesion and a strong sense of civic duty, as citizens were expected to provide their own weapons and armor and to fight for the defense of their polis.

The social organization of the polis was also shaped by the concept of citizenship. Citizenship was not simply a matter of residency; it was a privilege that conferred certain rights and responsibilities. Citizens had the right to participate in political assemblies, to vote on laws, and to hold public office. They also had the responsibility to serve in the military, to pay taxes, and to uphold the laws of the polis.

However, citizenship was not universally available. Women, slaves, and foreigners were typically excluded from citizenship, and even among male citizens, there were significant inequalities based on wealth and status. The tension between the ideal of citizenship and the reality of social inequality would be a recurring theme in Greek history.

The economic life of the polis was based primarily on agriculture, trade, and craftsmanship. Farmers cultivated the fertile plains surrounding the city, producing grain, olives, and grapes. Merchants traded with other poleis and with foreign lands, importing raw materials and luxury goods. Artisans produced a wide range of goods, including pottery, textiles, metalwork, and sculpture.

The polis was not just a political and economic entity; it was also a cultural center. Each polis had its own patron deity, its own festivals, and its own traditions. The Greeks shared a common language, a common religion, and a common cultural heritage, but they also maintained a strong sense of local identity. This combination of shared culture and local autonomy was a defining characteristic of the Greek world.

The emergence of the polis was a turning point in Greek history. It marked the beginning of a new era of political experimentation, intellectual innovation, and artistic creativity. The poleis would become the stage for some of the most important events in Western civilization, from the Persian Wars to the Peloponnesian War, from the philosophical debates of Socrates to the dramatic performances of Sophocles.

However, the polis was not without its limitations. The constant competition between the poleis led to frequent warfare and political instability. The limited size of the poleis made them vulnerable to larger empires. And the social inequalities within the poleis often led to internal conflict and unrest.

Despite these limitations, the polis represented a remarkable achievement in human history. It was a testament to the Greek spirit of innovation, self-governance, and civic duty. It laid the foundation for the development of democracy, individual liberty, and Western civilization.

As we move forward, we will delve into the specific characteristics of some of the most important poleis, examining their political systems, their social structures, and their cultural achievements. We will explore the unique qualities of Sparta, with its rigid military discipline, and Athens, the birthplace of democracy. We will examine the impact of Homer and the shaping of the Greek identity through the Iliad and the Odyssey. And we will consider the legacy of the polis in the modern world.

But before we proceed, let us pause for a moment to consider the enduring mystery of the Dark Ages. What can we learn from this period of upheaval and transition? What does it tell us about the fragility of civilizations and the resilience of the human spirit? And what lessons can we draw from the rise of the polis for our own time?

The answers to these questions, I suspect, lie not just in the archaeological record or the ancient texts, but also in our own capacity for empathy, imagination, and critical thinking. And as we turn the page, we will find ourselves drawn ever deeper into the breath of bronze and stone, into the heart of Ancient Greece. But what of the great figures who rose from this era and what ghosts from the past would haunt their every step. This is what we shall learn next.

The Abandoned City

The Rise of the Polis

Chapter 4: Homer and the Shaping of the Greek Identity

The story of Greece, as we have seen, emerges from the mists of the Bronze Age and the subsequent period of upheaval we call the Dark Ages. But history is more than just a chronicle of events, of migrations and collapses. It is also the story of ideas, of values, of the shared narratives that bind a people together. And no figure is more central to understanding the formation of Greek identity than Homer, the purported author of the Iliad and the Odyssey.

The very existence of Homer is shrouded in mystery. Was he a single individual, a blind bard wandering the Aegean, reciting tales of gods and heroes? Or was “Homer” a convenient name for a collective of storytellers, each contributing to a tradition that evolved over centuries? The truth may never be known. What is certain is that the Iliad and the Odyssey, whether the work of one man or many, became foundational texts for Greek culture, shaping their worldview, their moral compass, and their understanding of themselves in relation to the world around them.

These epic poems, passed down orally for generations before being committed to writing (likely in the 8th century BCE, though the exact dating remains a subject of scholarly debate), are not simply entertaining stories. They are repositories of Greek values, beliefs, and social norms. They offer glimpses into the world of the Mycenaean past, filtered through the lens of the Dark Ages, reflecting the anxieties and aspirations of a society struggling to rebuild itself after a period of profound disruption. The heroes of the Iliad and the Odyssey became exemplars for generations of Greeks, their virtues and flaws serving as both models and cautionary tales.

Let us consider the Iliad, the story of the Trojan War. At its surface, it is a tale of siege and battle, of heroes clashing on the plains of Troy. But beneath the surface lies a complex exploration of themes such as honor, glory, fate, and the destructive consequences of pride. Achilles, the greatest warrior of the Achaeans (as the Greeks were often called in Homer), is a figure of immense strength and skill, but also of profound vulnerability. His rage, fueled by Agamemnon's insult, nearly costs the Achaeans the war. He withdraws from battle, consumed by his own wounded pride, demonstrating the devastating consequences of unchecked emotion.

Homer does not shy away from portraying the darker aspects of human nature. The Iliad is filled with scenes of violence, brutality, and suffering. The gods themselves are often depicted as capricious and self-serving, intervening in human affairs for their own amusement or advantage. Yet, amidst the carnage, we also see glimpses of compassion, loyalty, and love. Hector, the Trojan prince, is a noble and courageous warrior, but also a devoted husband and father. His final farewell to Andromache and his son Astyanax is one of the most poignant scenes in the Iliad, reminding us of the human cost of war.

The Iliad establishes a warrior ethos that permeated much of Greek society. The pursuit of kleos (glory, renown) was a driving force for many Greek men, who sought to achieve immortality through their deeds in battle. This emphasis on military prowess and heroic achievement shaped the values of the aristocracy and influenced the development of the hoplite phalanx, the citizen army that would become the backbone of Greek military power.

The Odyssey, in contrast to the Iliad's focus on war, is a tale of homecoming, of resilience, and of the triumph of cunning over brute force. Odysseus, the king of Ithaca, spends ten years wandering the seas after the Trojan War, facing countless perils and temptations before finally returning to his wife Penelope and his son Telemachus.

The Odyssey is a journey of self-discovery, as Odysseus is forced to confront his own weaknesses and limitations. He encounters mythical creatures such as the Cyclops Polyphemus, the sorceress Circe, and the seductive Sirens, each representing a different kind of threat to his physical and moral well-being. His encounters with these fantastical beings, I would argue, are not merely whimsical diversions, but allegorical representations of the challenges faced by individuals navigating a complex and often treacherous world.

Penelope, Odysseus's wife, is a figure of remarkable strength and cunning in her own right. She fends off the advances of numerous suitors who seek to usurp Odysseus's throne, remaining steadfastly loyal to her husband despite his prolonged absence. Her weaving and unweaving of Laertes' shroud is a brilliant act of deception, a testament to her intelligence and resourcefulness. She embodies the ideal of the faithful and virtuous wife, a model for generations of Greek women.

The Odyssey also explores the themes of justice and revenge. Upon his return to Ithaca, Odysseus, with the help of Telemachus and the loyal swineherd Eumaeus, slaughters the suitors who have been plundering his palace and harassing his wife. This act of violence, while perhaps morally questionable from a modern perspective, is presented as a just retribution for their transgressions. It restores order to Ithaca and reaffirms Odysseus's authority as king.

The impact of the Iliad and the Odyssey on Greek culture extended far beyond the battlefield and the palace. These poems became a source of moral guidance, shaping the ethical values of Greek society. They provided models of virtuous behavior, such as courage, loyalty, and piety, and warned against the dangers of hubris, greed, and treachery. They also served as a common cultural touchstone, uniting the disparate city-states of Greece through a shared sense of identity.

The epics were recited at festivals and public gatherings, their stories becoming deeply ingrained in the collective consciousness of the Greek people. They were studied in schools, their verses memorized and analyzed. They inspired artists, sculptors, and playwrights, who drew upon their themes and characters to create new works of art. The influence of Homer is pervasive throughout Greek culture, shaping its literature, its art, and its worldview.

Moreover, the Iliad and the Odyssey contributed to the development of the Greek language. The Homeric dialect, a composite of various regional dialects, became the standard literary language of Greece, used by poets, historians, and philosophers for centuries. The epics also helped to standardize Greek orthography, contributing to the development of a written language that could be used to record and transmit knowledge.

It is important to acknowledge, however, that the Homeric epics also reflect the social inequalities of ancient Greek society. They glorify the warrior class, often at the expense of ordinary farmers and laborers. They portray women in limited roles, primarily as wives and mothers. They take slavery for granted, depicting slaves as mere property, devoid of human dignity. While celebrating the achievements of the Greek heroes, we must not ignore the darker aspects of the society that produced these epics.

Nevertheless, the enduring legacy of Homer is undeniable. The Iliad and the Odyssey remain two of the greatest works of literature ever written, their themes and characters continuing to resonate with readers across cultures and across time. They offer a profound glimpse into the world of ancient Greece, shaping our understanding of its values, its beliefs, and its enduring contributions to Western civilization.

As we move forward, we must consider how this Homeric vision played out in the various poleis. We have already touched upon the rise of these city-states, but next, we turn our focus to two of the most distinct and influential: Sparta, with its dedication to discipline and the art of war, and Athens, the birthplace of democracy. The contrasting paths they forged would define much of the history that followed, and the echoes of their rivalry still resonate today.

Homer Reciting His Epics

Achilles' Rage

Chapter 5: Sparta: Discipline and the Art of War

The word "Sparta" conjures immediate images: stoic warriors, rigorous training, and unwavering loyalty to the state. But to truly understand Sparta, we must move beyond these iconic images and delve into the complexities of its unique society, a society deliberately crafted to prioritize military strength above all else. Sparta offers a stark contrast to Athens, a fascinating counterpoint in the tapestry of ancient Greece. While Athens nurtured democracy, philosophy, and the arts, Sparta dedicated itself to the art of war, creating a social and political system unlike any other in the ancient world. It is a study in societal engineering, for better and, as we shall see, for worse.

The origins of Spartan society are shrouded in myth and legend, attributed to a figure named Lycurgus. Whether Lycurgus was a single historical individual or a composite figure representing a series of reforms remains a matter of debate. Regardless, the "Great Rhetra," the Spartan constitution attributed to Lycurgus, shaped Spartan life for centuries. This constitution emphasized austerity, discipline, and collective identity. Its aim was simple: to create a society of warriors capable of defending Sparta's territory and maintaining its dominance in the Peloponnese.

The Spartan social structure was rigidly hierarchical. At the top were the Spartiates, the full citizens who dedicated their lives to military service. Below them were the Perioeci, the "dwellers around," who were free but lacked political rights. They engaged in trade, crafts, and agriculture, providing essential goods and services to the Spartan economy. At the bottom of the social ladder were the Helots, the state-owned serfs who were tied to the land and forced to work for the Spartiates. The Helots were primarily descendants of the Messenians, a people conquered by Sparta in the 8th century BCE. Their subjugation and constant threat of rebellion were a constant preoccupation for the Spartans, shaping their militaristic mindset and their need for constant vigilance.

The Spartan system, then, rested on a foundation of conquest and oppression. The Spartiates maintained their privileged position through force, suppressing any dissent or challenge to their authority. This created a society marked by fear and paranoia, where individual expression was stifled and conformity was enforced. The very success of Sparta, its military prowess and its stability, was built upon the backs of the Helots, a fact that is often overlooked in romanticized accounts of Spartan valor.

The defining characteristic of Spartan life was the agoge, the state-sponsored system of education and training for young boys. From the age of seven, Spartan boys were taken from their families and placed in communal barracks, where they were subjected to a rigorous regimen of physical and mental discipline. The agoge was designed to instill obedience, endurance, and a fierce loyalty to the state.

The boys were taught to endure hardship without complaint. They were given minimal food and clothing, encouraged to steal to supplement their rations (though punished if caught), and subjected to brutal physical tests. The aim was not simply to create strong soldiers, but to cultivate a particular kind of character: stoic, resourceful, and utterly devoted to the Spartan ideal. Plutarch, in his Life of Lycurgus, describes the agoge in vivid detail, noting that "they were taught to steal adroitly, that they might be more expert in procuring necessaries, and to be hardy and vigilant, that they might not be surprised in their theft." This emphasis on cunning and deception, while seemingly contradictory to the Spartan ideal of honor, was seen as a valuable asset in warfare.

The agoge also emphasized physical fitness. Boys were constantly engaged in wrestling, running, and other athletic activities. They were taught to fight as a unit, forming the phalanx, the heavily armed infantry formation that was the backbone of the Spartan army. The phalanx relied on discipline, coordination, and unwavering courage. Each hoplite (heavy infantryman) stood shoulder to shoulder with his comrades, forming an impenetrable wall of shields and spears. The success of the phalanx depended on the willingness of each individual to sacrifice himself for the good of the group.

The Spartans did not neglect intellectual training entirely, but it was secondary to physical and military preparation. Boys were taught to read and write, but their education focused primarily on memorizing poetry and songs that celebrated Spartan values and military achievements. They were also taught to speak concisely and directly, a style known as "laconic," after Laconia, the region of Greece where Sparta was located. This emphasis on brevity and directness reflected the Spartan disdain for unnecessary words and their focus on action.

The Spartan military system was not simply a matter of training and equipment. It was a way of life. Spartiates spent their entire adult lives in military service, living in communal barracks and eating at common messes (syssitia). They were forbidden from engaging in trade or agriculture, relying instead on the labor of the Helots and the Perioeci. This allowed them to devote all their time and energy to military pursuits, making them the most formidable fighting force in Greece.

The syssitia played a crucial role in fostering camaraderie and loyalty among the Spartiates. Each mess consisted of a group of about fifteen men who ate together regularly. The meals were simple and austere, reflecting the Spartan emphasis on frugality. Plutarch recounts an anecdote about a king of Pontus who visited a Spartan syssitia and found the meal so unappetizing that he could not eat it. The Spartan cook replied, "Then of course you would not have cared for our black broth either." This "black broth," a concoction of pork, blood, and vinegar, was a staple of the Spartan diet, and its unpalatability was seen as a virtue, a testament to Spartan indifference to luxury.

The Spartan army was renowned for its discipline, its courage, and its effectiveness. The Spartans were masters of hoplite warfare, and their phalanx was virtually unbeatable on the open battlefield. Their victories at Thermopylae (though ultimately a defeat, a testament to their unwavering courage) and Plataea secured their reputation as the defenders of Greece against the Persian Empire. Thucydides, in his History of the Peloponnesian War, describes the Spartans as being "slow to act, and cautious in their deliberations, but when once they have made up their minds, they are not easily turned from their purpose." This combination of deliberation and determination made them formidable adversaries.

However, the Spartan military system had its limitations. The Spartans were primarily land-based warriors and lacked a strong navy. This limited their ability to project power overseas and made them vulnerable to naval attacks. Their reliance on the Helots also created a constant security threat, requiring them to maintain a large force at home to suppress any potential rebellion.

Spartan society was highly regulated in all aspects of life, not just military training. Marriage, for example, was strictly controlled by the state. Spartan women were expected to be strong and healthy, capable of bearing strong and healthy children. They received physical training similar to that of the men, participating in running, wrestling, and other athletic activities. Unlike women in other Greek city-states, Spartan women enjoyed a relatively high degree of freedom and independence. They could own property, manage their own finances, and participate in public discussions. Plutarch notes that Spartan women "exercised a great deal of authority in their homes, and spoke their minds freely on public matters."

However, this freedom was not without its constraints. Spartan women were expected to prioritize the needs of the state above all else. Their primary duty was to produce healthy sons who would become warriors. They were encouraged to be ruthless in their devotion to Sparta. Plutarch recounts an anecdote about a Spartan mother who sent her son off to war with the words, "Return with your shield, or on it." This meant that he should either return victorious or die fighting, rather than surrender and bring shame upon his family and his city.

The Spartan emphasis on collective identity and military strength came at a cost. Individual expression was stifled, intellectual pursuits were discouraged, and artistic creativity was limited. The Spartans produced no great philosophers, poets, or artists. Their legacy lies primarily in their military achievements and their unique social system, a system that was both admired and reviled by other Greeks.

The question remains: Was Sparta truly a successful society? Its military strength was undeniable, but its rigid social structure and its reliance on oppression created a society that was both admirable and deeply flawed. As we continue our journey through ancient Greece, we will see how the Spartan model influenced other city-states and how its legacy continues to shape our understanding of warfare, politics, and the human condition.

The Spartan model, despite its successes in creating a powerful military force, ultimately proved unsustainable. The constant need to suppress the Helots, the limited number of Spartiates, and the lack of economic diversity weakened Sparta over time. In the 4th century BCE, Sparta suffered a series of defeats at the hands of Thebes, a rising power in central Greece. The Battle of Leuctra in 371 BCE marked the beginning of the end for Spartan dominance. The Theban general Epaminondas, using innovative military tactics, shattered the Spartan phalanx and liberated the Messenians, freeing the Helots and depriving Sparta of its primary source of labor.

The decline of Sparta serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of excessive militarization and the importance of social justice. A society that prioritizes military strength above all else, that suppresses individual expression, and that relies on oppression cannot ultimately thrive. Sparta's legacy is complex and multifaceted, a reminder that even the most powerful societies are vulnerable to internal contradictions and external challenges.

As we turn our attention to Athens, the birthplace of democracy, we will see a different model of social and political organization, one that emphasized individual liberty, intellectual pursuits, and artistic creativity. The contrast between Sparta and Athens is stark, but both city-states played a crucial role in shaping the course of ancient Greek history. They represent two different paths, two different visions of what a society can be. And in their successes and failures, we can find valuable lessons for our own time.

But before we leave Sparta entirely, a question lingers: What if the Spartan ideal, stripped of its brutal subjugation of the Helots, had been tempered with a greater appreciation for intellectual and artistic pursuits? Could a society have emerged that combined Spartan discipline with Athenian creativity? This tantalizing "what if" will continue to haunt us as we explore the vibrant and turbulent world of Ancient Greece, as we turn our focus to the city that dared to imagine a different kind of world – a world governed not by the spear, but by the word. The next chapter awaits: "Athens: The Birthplace of Democracy," where we will explore the radical experiment that changed the course of history.

A Spartan Woman's Strength

Chapter 6: Athens: The Birthplace of Democracy

The very air in Athens hums with a different energy than in Sparta. Where the Laconian landscape feels sculpted by discipline and the relentless pursuit of military perfection, Attica breathes with a restless, inquisitive spirit. The sun, filtered through the haze of olive groves, seems to illuminate not just the land, but also the very ideas that sprung forth from it. To understand Athens, we must understand the very soil that nurtured its unique brand of democracy, a system both revolutionary and, as we shall see, deeply flawed. It is a system of governance that continues to resonate, to inspire, and to provoke debate even today.

The origins of Athenian democracy are not as straightforward as a single, defining moment. Rather, it was a gradual evolution, a series of reforms and power struggles that unfolded over centuries. Early Athens, like many other Greek city-states, was ruled by a monarchy. Over time, however, power shifted to the aristocracy, the eupatridae, wealthy landowners who controlled the land and dominated the Areopagus, the council of elders. This oligarchical system, however, proved increasingly unpopular, particularly among the lower classes, who felt disenfranchised and burdened by debt.

The seeds of democratic change were sown in the late 7th and early 6th centuries BCE, a period marked by social unrest and economic hardship. The first significant step towards reform came with the appointment of Draco, an archon (magistrate) tasked with codifying Athenian law. Draco’s laws, while notoriously harsh (hence the term "draconian"), were nonetheless significant in that they were written down and made public, rather than being interpreted arbitrarily by the aristocracy. However, Draco’s laws did little to address the underlying economic inequalities that fueled social unrest. Debt bondage, where individuals were forced into slavery to pay off their debts, remained a widespread practice.

It was Solon, appointed archon in 594 BCE, who truly laid the foundation for Athenian democracy. Solon was a statesman, a poet, and a man of immense wisdom and integrity. Recognizing the deep divisions within Athenian society, he embarked on a series of radical reforms aimed at alleviating economic hardship and expanding political participation. His most immediate act was the seisachtheia, the "shaking off of burdens," which abolished debt bondage and freed those who had been enslaved for debt. He also cancelled existing debts and prohibited future loans secured by personal freedom. This act alone dramatically altered the social landscape of Athens, preventing the concentration of land and wealth in the hands of a few.

But Solon's reforms went far beyond economic relief. He restructured Athenian society into four classes based on wealth, rather than birth. While the eupatridae remained at the top, Solon granted political rights to the lower classes, including the right to participate in the Assembly, the ekklesia, where citizens could debate and vote on laws. He also established the Council of Four Hundred, the boule, composed of members from each of the four classes, which prepared legislation for the Assembly. These reforms, while not creating a fully democratic system, significantly broadened political participation and laid the groundwork for future developments.

Solon himself recognized the limitations of his reforms. He famously stated that he had given the Athenians "the best laws they were able to bear." He understood that Athenian society was not yet ready for a fully democratic system, and that gradual change was necessary to prevent chaos and instability. After implementing his reforms, Solon left Athens for ten years, allowing the Athenians to experiment with their new system without his direct influence. This self-imposed exile demonstrated Solon’s commitment to the rule of law and his belief in the importance of allowing the Athenians to govern themselves.

Despite Solon’s efforts, Athenian society remained turbulent. The decades following his reforms were marked by factional strife and political instability. The aristocracy continued to vie for power, while the lower classes demanded greater political rights. This period of unrest culminated in the rise of Peisistratus, a popular general who seized power in 561 BCE and established a tyranny.

Peisistratus, despite being a tyrant, ruled with considerable skill and moderation. He maintained Solon’s laws and institutions, but used his power to promote economic development and cultural achievements. He fostered trade, supported the arts, and commissioned public works projects, such as the construction of new temples and the improvement of Athens’ water supply. He also established the Panathenaic Games, a major religious and athletic festival that celebrated Athenian identity.

Peisistratus’ rule was interrupted by periods of exile and resistance from the aristocracy, but he ultimately maintained control of Athens until his death in 527 BCE. His sons, Hippias and Hipparchus, succeeded him, but their rule proved increasingly oppressive. In 514 BCE, Hipparchus was assassinated, and Hippias became increasingly paranoid and tyrannical. This led to widespread discontent and ultimately to the overthrow of the tyranny in 510 BCE, with the help of Spartan forces.

The overthrow of the Peisistratid tyranny marked a turning point in Athenian history. With the aristocracy discredited and the lower classes emboldened, the stage was set for the final triumph of democracy.

It was Cleisthenes, an Athenian aristocrat, who finally established Athenian democracy in its fully realized form. Cleisthenes recognized that the key to preventing future tyranny was to break the power of the aristocracy and to empower the people. He implemented a series of radical reforms that fundamentally reshaped Athenian society and politics.

His most significant reform was the creation of ten new tribes, or phylai, based on geographical location rather than kinship or social class. This effectively broke the power of the aristocratic families, who had traditionally dominated Athenian politics through their control of kinship groups. Each tribe was composed of demes, local communities that served as the basic units of Athenian citizenship. This system ensured that all citizens, regardless of their social status, had an equal voice in Athenian politics.

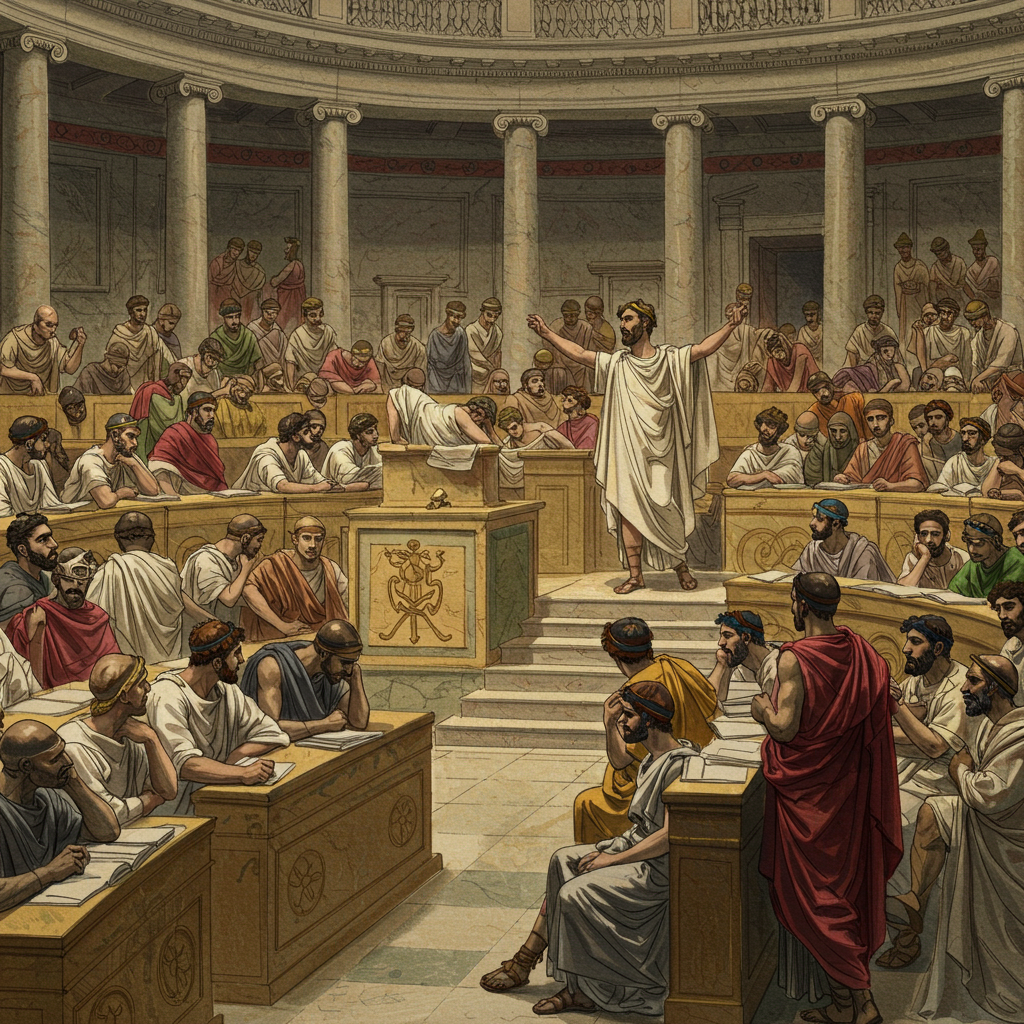

Cleisthenes also strengthened the boule, the Council of Five Hundred, by increasing its membership and assigning members from each of the ten tribes. The boule prepared legislation for the Assembly and oversaw the day-to-day administration of Athens. He further empowered the Assembly, the ekklesia, by granting it the power to make all major decisions, including the declaration of war, the ratification of treaties, and the election of officials.

Perhaps Cleisthenes' most innovative reform was the introduction of ostracism, a process by which the Athenians could exile a citizen who was deemed to be a threat to democracy. Once a year, the Athenians would gather in the agora and write the name of the person they wished to ostracize on a potsherd, or ostrakon. If a citizen received enough votes, he was exiled from Athens for ten years, without losing his property or citizenship. Ostracism was intended to prevent the rise of tyranny by removing potential threats to democracy before they could gain too much power. It was a somewhat brutal, but ultimately effective, mechanism for safeguarding Athenian democracy.

The reforms of Cleisthenes transformed Athens into a truly democratic state. For the first time in history, citizens had the power to govern themselves, to make decisions about their own lives and their own future. Athenian democracy, however, was not without its limitations. Women, slaves, and metics were excluded from citizenship and had no political rights. Athenian democracy was also susceptible to manipulation and demagoguery. Skilled orators could sway the Assembly with their words, often appealing to emotions rather than reason.

The Golden Age of Athens, under the leadership of Pericles in the 5th century BCE, represents the zenith of Athenian democracy. Pericles, a brilliant statesman and orator, led Athens to unprecedented heights of power, prosperity, and cultural achievement. He used his influence to further strengthen Athenian democracy, ensuring that all citizens had the opportunity to participate in government. He introduced pay for jury service, allowing poorer citizens to serve on juries and participate in the administration of justice. He also commissioned the construction of the Parthenon and other magnificent buildings, transforming Athens into a city of unparalleled beauty and grandeur.

However, even during the Golden Age, the seeds of Athenian decline were being sown. The Peloponnesian War, a protracted conflict between Athens and Sparta, exposed the weaknesses of Athenian democracy. The war led to internal divisions, economic hardship, and ultimately to the defeat of Athens in 404 BCE. The defeat of Athens marked the end of its Golden Age and the beginning of a long period of decline.

The legacy of Athenian democracy is complex and multifaceted. It was a revolutionary experiment in self-government, but it was also a system with significant limitations. It inspired countless generations with its ideals of liberty, equality, and popular sovereignty, but it also served as a cautionary tale about the dangers of demagoguery, factionalism, and imperial ambition. As we move forward, examining the Delian League and the seeds it sowed for Athenian Imperialism, we must ask ourselves: can democracy truly thrive without succumbing to the temptations of power?

The Athenian Assembly

Aspasia's Salon

Chapter 7: The Persian Wars: A Clash of Civilizations

The Aegean wind carried whispers of change, a restlessness that rippled through the poleis like a tremor before an earthquake. The sixth century BCE had witnessed the rise of the Persian Empire, a vast and formidable power stretching from the borders of India to the shores of the Hellespont. Their ambition, fueled by conquest and a seemingly insatiable hunger for territory, now turned its gaze westward, towards the fragmented, yet fiercely independent, Greek world. The clash that ensued was not merely a conflict of armies, but a collision of civilizations, a test of wills that would determine the fate of Greece and, arguably, the future of Western civilization.

The seeds of conflict were sown in Ionia, a region on the western coast of Asia Minor populated by Greek city-states. These Ionian Greeks, culturally akin to their counterparts on the mainland, had fallen under Persian rule. Resentment simmered under the surface, fueled by heavy taxation, autocratic rule, and the imposition of Persian customs. In 499 BCE, this resentment boiled over into open rebellion. Aristagoras, the tyrant of Miletus, instigated the Ionian Revolt, seeking to throw off the Persian yoke. He appealed to the mainland Greeks for assistance, a plea that was largely ignored. Only Athens and Eretria, a city on the island of Euboea, answered the call, sending a small force to aid the rebels.

This intervention, though limited in scope, was enough to enrage Darius I, the Persian king. The Athenians and Eretrians participated in the sack of Sardis, the Persian satrapal capital, an act of defiance that Darius would neither forgive nor forget. The Ionian Revolt was ultimately crushed by the Persians, who brutally suppressed the rebellion and reasserted their control over the region. But Darius, ever the pragmatist, understood that the mainland Greeks, particularly Athens, posed a potential threat to his empire. He resolved to punish them for their interference and to secure the western frontier of his vast domain.

In 492 BCE, Darius dispatched an expeditionary force under the command of his son-in-law, Mardonius, to subdue Greece. Mardonius led his army through Thrace and Macedonia, forcing the local tribes to submit to Persian rule. However, disaster struck as the Persian fleet was caught in a violent storm off the coast of Mount Athos, resulting in heavy losses. Mardonius was forced to retreat, and the invasion was aborted. This setback, however, only strengthened Darius' resolve. He began preparations for a larger and more decisive invasion, one that would bring Greece firmly under Persian control.

Two years later, in 490 BCE, Darius launched his second invasion of Greece, this time targeting Athens and Eretria directly. He sent a fleet across the Aegean Sea, carrying a substantial army under the command of Datis and Artaphernes. The Persians landed on the island of Euboea and swiftly captured Eretria, exacting a brutal retribution for their earlier involvement in the sack of Sardis. The city was razed to the ground, and its inhabitants were enslaved.

The Persian fleet then sailed across the narrow straits to the plain of Marathon, a coastal area northeast of Athens. The Athenians, faced with imminent invasion, sent a desperate plea for assistance to Sparta, the dominant military power in the Peloponnese. The Spartans, bound by religious obligations, delayed their response, claiming they could not march until after the full moon. The Athenians, therefore, were left to face the Persian threat with only a small contingent of Plataeans as allies.

The Athenian army, led by ten generals, including the experienced Miltiades, marched to Marathon to confront the Persians. Miltiades, recognizing the strategic importance of the plain, convinced the other generals to engage the enemy in battle. The Athenian army, though outnumbered, was composed of highly disciplined hoplites, heavily armed infantry soldiers who fought in a tightly packed formation known as the phalanx.

The Battle of Marathon, fought in the sweltering heat of August, was a pivotal moment in Greek history. The Athenian army, positioned on the high ground overlooking the plain, launched a surprise attack on the Persian forces. The Athenian phalanx, with its superior discipline and weaponry, charged down the slope and crashed into the Persian lines. The Persians, accustomed to fighting lightly armed opponents in open terrain, were caught off guard by the ferocity of the Athenian assault.

The battle raged for hours, a brutal clash of bronze and steel. The Athenian hoplites, fighting for their freedom and their city, displayed extraordinary courage and determination. Miltiades, a brilliant tactician, reinforced the wings of his army, weakening the center. As the Persians pushed forward in the center, the reinforced wings enveloped them, creating a deadly trap. The Persian army, surrounded and overwhelmed, began to break ranks and flee towards their ships.

The Athenians pursued the fleeing Persians, inflicting heavy casualties. The Persians, in their haste to escape, abandoned much of their equipment and supplies. The battle was a decisive victory for the Athenians, who had proven that the seemingly invincible Persian army could be defeated. According to tradition, Pheidippides, an Athenian messenger, ran from Marathon to Athens to announce the victory, proclaiming "Νενικήκαμεν!" (Nenikēkamen! – "We have won!"), before collapsing and dying.

The Battle of Marathon had a profound impact on Greek morale and self-confidence. It demonstrated that the Greek city-states, even when outnumbered, could resist the might of the Persian Empire. The victory instilled a sense of unity and purpose among the Greeks, galvanizing them to prepare for future conflicts. Darius, though defeated, did not abandon his ambitions. He began preparations for a third, even larger, invasion of Greece, determined to avenge his defeat and bring the Greek world under Persian control. However, Darius died in 486 BCE, leaving the task of conquering Greece to his son, Xerxes.

Xerxes, inheriting his father's ambition and resources, spent several years preparing for the invasion. He amassed a vast army, said to number in the hundreds of thousands, drawn from all corners of the Persian Empire. He also assembled a massive fleet to support his land forces. Xerxes's preparations were meticulous and extensive, reflecting the immense scale of his ambition. He even ordered the construction of a bridge across the Hellespont, a feat of engineering that astounded the ancient world.

News of Xerxes's preparations reached Greece, causing widespread alarm and anxiety. The Greek city-states, still fragmented and often at odds with one another, were faced with the daunting prospect of confronting the largest army the world had ever seen. Some city-states, fearing the might of Persia, chose to submit to Xerxes without resistance. Others, led by Athens and Sparta, resolved to defend their freedom at all costs.

In 481 BCE, representatives from various Greek city-states met at Corinth to form a defensive alliance, known as the Hellenic League. This alliance, though fragile and often plagued by internal divisions, represented a significant step towards Greek unity. The Greeks agreed to put aside their differences and to cooperate in the defense of their homeland. Sparta was granted the overall command of the allied forces, reflecting its military prowess and its reputation for discipline and courage.

The stage was set for the ultimate clash between Greece and Persia, a conflict that would test the resilience of the Greek spirit and determine the course of Western history. The battles that followed would become legendary, tales of heroism and sacrifice that would echo through the ages. The struggle for freedom had begun.

The year 480 BCE witnessed the full fury of Xerxes' invasion unleashed upon Greece. The Persian army, a seemingly endless tide of soldiers, marched through Thrace and Macedonia, encountering little resistance. The Persian fleet, sailing along the coast, provided logistical support and threatened the Greek cities along the Aegean Sea.

The first major battle of the invasion took place at Thermopylae, a narrow pass between the mountains and the sea in central Greece. A small force of Greek soldiers, led by King Leonidas of Sparta, decided to make a stand at Thermopylae, hoping to delay the Persian advance and buy time for the rest of Greece to prepare for the invasion.

Leonidas, a warrior king in the truest sense, chose 300 of his finest Spartan warriors to accompany him to Thermopylae. These men, handpicked for their courage and skill, were prepared to fight to the death. They were joined by several thousand other Greek soldiers from various city-states, forming a combined force of around 7,000 men.

The Greeks positioned themselves in the narrowest part of the pass, hoping to use the terrain to their advantage. The Persian army, vastly outnumbering the Greeks, arrived at Thermopylae and demanded their surrender. Leonidas famously replied, "Μολὼν λαβέ" (Molon labe – "Come and get them").

The Battle of Thermopylae lasted for three days, a desperate struggle against overwhelming odds. The Greek soldiers, fighting in a tight formation, repelled repeated Persian assaults. The Spartan hoplites, with their superior training and discipline, proved to be particularly effective in the narrow confines of the pass. The Persians, unable to deploy their full numbers, suffered heavy casualties.

However, a Greek traitor, Ephialtes, revealed a secret path that allowed the Persians to outflank the Greek position. Leonidas, realizing that his forces were about to be encircled, dismissed the majority of his troops, allowing them to retreat and regroup. He remained at Thermopylae with his 300 Spartans, along with a small contingent of Thespians and Thebans, determined to fight to the death.

The final stand at Thermopylae was an act of unparalleled heroism. The Spartans, surrounded by the enemy, fought with a ferocity that astonished the Persians. Leonidas himself fell in battle, but his men continued to fight over his body, refusing to yield. The last of the Spartans were eventually overwhelmed and killed, but their sacrifice had bought valuable time for the rest of Greece.

The Battle of Thermopylae, though a defeat for the Greeks, became a symbol of courage, resistance, and self-sacrifice. The story of Leonidas and his 300 Spartans inspired the Greeks to continue the fight against the Persian invaders. As Theron writes, "Thermopylae was not a victory in the conventional sense, but it was a triumph of the human spirit, a testament to the power of courage and the enduring value of freedom."

The Persian army, now able to advance through Thermopylae, marched south towards Athens. The Athenians, led by Themistocles, decided to abandon their city and evacuate its population to the island of Salamis. Xerxes entered Athens and, in a fit of rage, ordered the Acropolis to be burned and the temples to be destroyed.

The fate of Greece now rested on the outcome of the naval battle that would soon take place in the straits of Salamis. Themistocles, a brilliant naval strategist, understood that the Greek fleet, though smaller than the Persian fleet, could use the narrow straits to their advantage. He devised a plan to lure the Persian fleet into the straits and engage them in a decisive battle. What Themistocles did next, however, was a gamble that could have cost the Greeks everything…

Battle of Thermopylae

The Naval Battle of Salamis

Chapter 8: The Golden Age of Athens: Art, Philosophy, and Drama

The victory at Marathon, and the subsequent triumph over Xerxes’ massive invasion force, instilled in the Greeks, particularly the Athenians, a sense of unprecedented confidence and purpose. The threat from the East, though never entirely extinguished, had been repelled, and the poleis could turn their attention inward, to rebuilding, reforming, and, in the case of Athens, to embarking on a period of cultural and intellectual flourishing that would forever be known as the Golden Age. This era, roughly spanning the fifth century BCE, represents a high-water mark in human achievement, a testament to the power of human ingenuity and creativity when nurtured by a relatively stable political and economic environment. However, as we shall see, even this golden age was not without its shadows, its contradictions, and its inherent vulnerabilities.

The architect of much of this Athenian renaissance was Pericles, whom we encountered in the previous chapter. His leadership, spanning over three decades, was characterized by a shrewd understanding of Athenian character, a commitment to democratic principles (albeit within the limitations of the time), and a grand vision for the city’s future. He recognized that Athens' strength lay not just in its military prowess or its economic power, but also in its cultural influence, its ability to inspire and to attract the best minds from across the Greek world. Thus, he embarked on an ambitious building program, transforming the Acropolis into a magnificent testament to Athenian power and artistic skill.

The most iconic structure of this building program was, of course, the Parthenon, the temple dedicated to Athena, the patron goddess of Athens. This Doric temple, constructed of gleaming white marble, was a masterpiece of architectural design and engineering. Its proportions were meticulously calculated to create a sense of harmony and balance, and its sculptural decorations, overseen by the renowned Phidias, depicted scenes from Greek mythology, celebrating Athenian victories and showcasing the city's artistic prowess. But the Parthenon was more than just a beautiful building; it was a symbol of Athenian power, a visual statement of the city's wealth, its ambition, and its commitment to its gods.

The Acropolis, however, was not the only beneficiary of Pericles' building program. The Propylaea, the monumental gateway to the Acropolis, was constructed to provide a fitting entrance to the sacred precinct. The Erechtheion, a complex and asymmetrical temple dedicated to multiple deities, including Athena Polias, Poseidon, and Erechtheus, was built to replace an earlier temple destroyed during the Persian Wars. The Odeon of Pericles, a covered theater, was constructed to provide a venue for musical performances. All of these buildings, and many others, contributed to the transformation of Athens into a city of unparalleled beauty and grandeur.

But the Golden Age was not just about magnificent buildings; it was also about the explosion of intellectual and artistic creativity that occurred within Athens. Philosophy, in particular, flourished during this period. Socrates, the enigmatic and unconventional philosopher whom we profiled earlier, roamed the streets of Athens, engaging in public debates and challenging conventional wisdom. His method of questioning, known as the Socratic Method, forced his interlocutors to examine their beliefs and to confront their own ignorance. He believed that "the unexamined life is not worth living," and he sought to awaken others to the importance of self-reflection and critical thinking.

Socrates, however, was not without his critics. His relentless questioning and his unconventional lifestyle often provoked resentment and suspicion. He was accused of corrupting the youth and of impiety, charges that ultimately led to his trial and execution. But even in death, Socrates' influence continued to grow. His teachings were preserved by his student, Plato, who founded the Academy, a school of philosophy that would become one of the most important centers of learning in the ancient world.

Plato, in turn, built upon Socrates' ideas, developing his own philosophical system, which emphasized the importance of reason, justice, and the pursuit of the ideal. His theory of Forms, which posited the existence of a realm of perfect and unchanging archetypes, had a profound impact on Western thought. Plato's student, Aristotle, further expanded the scope of Greek philosophy, making significant contributions to logic, ethics, politics, and natural science. Aristotle's Lyceum, another important school of philosophy, became a rival to Plato's Academy, fostering a spirit of intellectual competition and innovation.

The Golden Age was also a period of unparalleled achievement in the dramatic arts. Athenian tragedy and comedy reached their peak during this era, with playwrights such as Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, and Aristophanes producing masterpieces that continue to be performed and studied today.

Aeschylus, the earliest of the great tragedians, is known for his grand and heroic dramas, which often explored themes of fate, justice, and the consequences of human actions. His Oresteia trilogy, which tells the story of the curse on the House of Atreus, is a powerful exploration of the cycle of violence and the need for reconciliation.

Sophocles, considered by many to be the greatest of the tragedians, is known for his masterful characterization, his complex plots, and his profound insights into the human condition. His Oedipus Rex, which tells the story of a king who unknowingly fulfills a prophecy that he will kill his father and marry his mother, is a chilling exploration of fate, free will, and the limits of human knowledge.

Euripides, the most modern of the tragedians, is known for his realistic portrayal of human emotions, his questioning of traditional values, and his sympathetic depiction of women and slaves. His Medea, which tells the story of a woman who murders her own children in revenge for her husband's betrayal, is a shocking and disturbing exploration of the dark side of human nature.

While tragedy explored the depths of human suffering and the complexities of moral choice, comedy, as practiced by Aristophanes, offered a lighter, more satirical perspective on Athenian society. Aristophanes' plays were filled with witty dialogue, outrageous characters, and biting social commentary. He lampooned politicians, philosophers, and even the gods themselves, using humor as a weapon to challenge authority and to expose hypocrisy. His Lysistrata, which tells the story of Athenian women who go on a sex strike to force their husbands to end the Peloponnesian War, is a hilarious and thought-provoking critique of war and male aggression.

The dramatic festivals of Athens, particularly the City Dionysia, were major cultural events, attracting audiences from across the Greek world. Plays were performed in open-air theaters, often with elaborate costumes and masks. The performances were not just entertainment; they were also a form of civic education, providing a forum for exploring important social and political issues.

The Golden Age of Athens, then, was a remarkable period of cultural and intellectual flourishing, a time when human creativity reached new heights. But as I mentioned earlier, it was not without its shadows. The wealth and power of Athens were built on the backs of slaves and metics, who were denied the rights and privileges enjoyed by Athenian citizens. The exclusion of women from public life limited the potential of half the population. And the imperial ambitions of Athens, its desire to dominate the Greek world, ultimately led to the Peloponnesian War, a devastating conflict that would bring the Golden Age to an end. The seeds of its own destruction, it seems, were sown even in its most glorious moments.

The drums of war are already beginning to beat on the horizon, and in the next chapter, we will turn our attention to the growing tensions between Athens and Sparta, tensions that will soon erupt into a conflict that will forever alter the course of Greek history. Will Athens' hubris be its downfall? Or can it navigate the treacherous waters of inter-polis rivalry and maintain its position as the leading power in Greece? The answer, as Thucydides would tell us, lies in a meticulous examination of the events to come.

Construction of the Parthenon

A Performance of a Tragedy

Chapter 9: The Peloponnesian War: The Fall of an Empire

The air in Athens, once vibrant with the echoes of Pericles' soaring orations and the rhythmic clang of hammers building the Parthenon, began to thicken with a different kind of sound: the murmur of discontent, the sharpening of swords, the distant drumbeat of impending war. The Golden Age, that brief but brilliant flowering of Athenian culture and power, was about to be plunged into the long, brutal winter of the Peloponnesian War.

The conflict, spanning nearly three decades (431-404 BCE), was more than just a clash of arms; it was a fundamental struggle for dominance in the Greek world, a battle between two fundamentally different ideologies and ways of life. On one side stood Athens, the champion of democracy, intellectual innovation, and maritime power. On the other, Sparta, the bastion of oligarchy, military discipline, and land-based strength. The war would ultimately consume both empires, leaving a fractured and weakened Greece vulnerable to external threats.