The Shadow of the Eagle: Europe Under Napoleon, 1799-1815

Synopsis

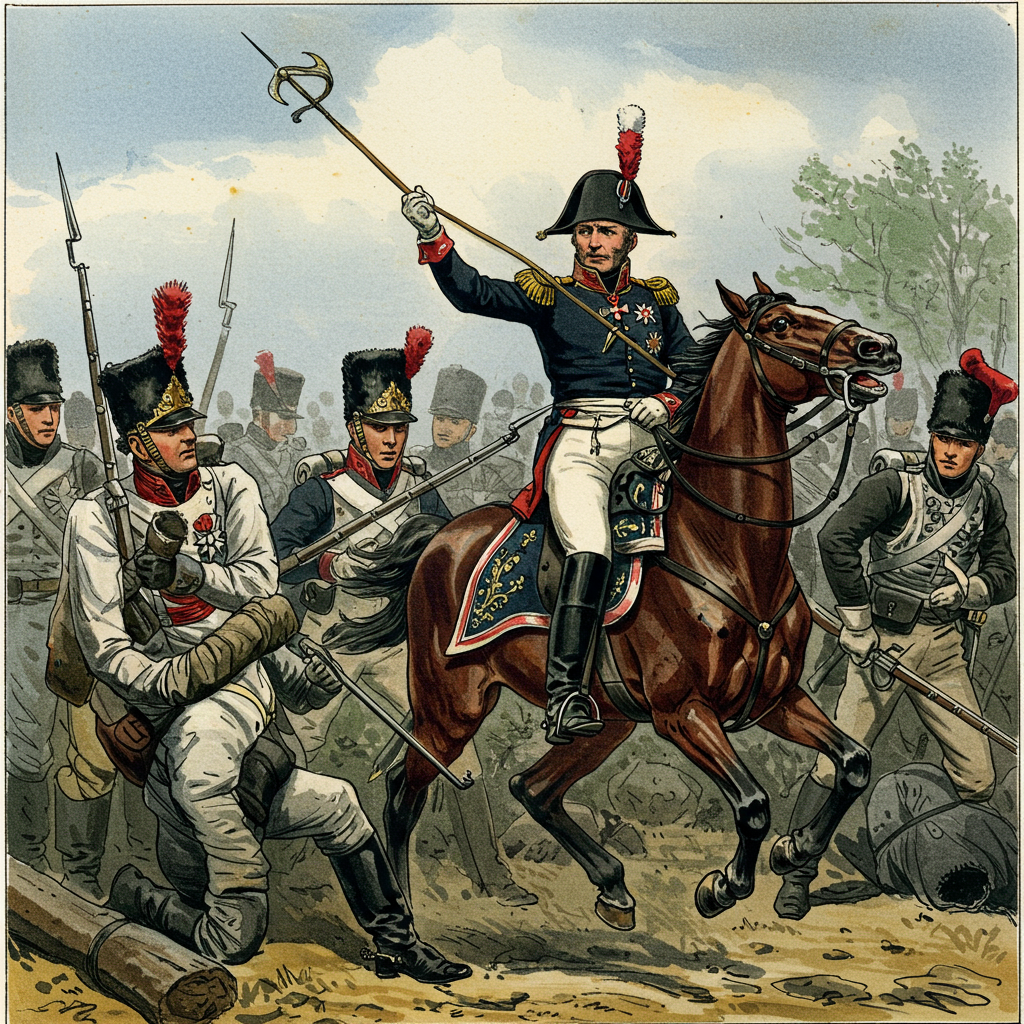

Dr. Alistair Blackwood's The Shadow of the Eagle offers a meticulously researched and nuanced account of the Napoleonic Wars, moving beyond simplistic narratives of heroic triumph and villainous defeat. The book examines the period from Napoleon Bonaparte's rise to power in 1799 to his final defeat at Waterloo in 1815, exploring the complex political, social, and economic forces that shaped Europe during this tumultuous era. Blackwood delves into the motivations of key figures, from Napoleon himself to his adversaries like Wellington and Tsar Alexander, analyzing their strategic decisions and personal ambitions within the broader context of shifting alliances and revolutionary ideologies.

The narrative emphasizes the human cost of the wars, drawing upon primary sources to illuminate the experiences of soldiers, civilians, and those caught between the warring empires. Blackwood challenges romanticized notions of warfare, highlighting the brutality, logistical challenges, and unintended consequences of Napoleon's campaigns. He examines the impact of the Continental System on European economies, the rise of nationalism as a potent force for both unity and division, and the lasting legacies of the Napoleonic era on the political landscape of the 19th century.

The Shadow of the Eagle aims to provide a comprehensive and balanced perspective on the Napoleonic Wars, acknowledging Napoleon's undeniable military genius while critically assessing his authoritarian tendencies and the devastating impact of his ambition on Europe. It is a book for readers seeking a deeper understanding of this pivotal period in European history, one that moves beyond simplistic narratives and embraces the complexities and contradictions of the past. Blackwood's "historical triangulation" approach ensures a multifaceted view, drawing from diverse sources to present a richer, more compelling picture of the era.

Table of Contents

- Chapter 1: The Inheritance of Revolution: Examines the state of Europe following the French Revolution, highlighting the political instability, social unrest, and ideological ferment that provided the backdrop for Napoleon's rise. It sets the stage by outlining the Directory's failures and the yearning for strong leadership.

- Chapter 2: Brumaire and the Consulate: Details Napoleon's coup d'état in 1799, analyzing the political maneuvering and popular support that allowed him to seize power. This chapter emphasizes the establishment of the Consulate and Napoleon's consolidation of authority.

- Chapter 3: Marengo and the Peace of Amiens: Focuses on Napoleon's military successes in Italy, culminating in the Battle of Marengo, and the subsequent Peace of Amiens. The chapter explores the brief period of peace and the underlying tensions that would soon lead to renewed conflict.

- Chapter 4: Emperor of the French: Analyzes Napoleon's decision to crown himself Emperor in 1804, exploring the motivations behind this move and its implications for the balance of power in Europe. The chapter also examines the establishment of the Napoleonic Code and its impact on legal systems.

- Chapter 5: Trafalgar and Austerlitz: Sea and Land: Contrasts Napoleon's defeat at the Battle of Trafalgar, which secured British naval supremacy, with his stunning victory at Austerlitz, solidifying his dominance on the continent. This chapter highlights the strategic importance of naval power and the limitations of Napoleon's reach.

- Chapter 6: The Confederation of the Rhine and the Fall of Prussia: Describes the formation of the Confederation of the Rhine, a French-dominated alliance of German states, and Prussia's subsequent defeat at the Battles of Jena-Auerstedt. The chapter examines the collapse of the Holy Roman Empire and the redrawing of the map of Germany.

- Chapter 7: Tilsit and the Continental System: Explores the Treaties of Tilsit, which marked the height of Napoleon's power, and the implementation of the Continental System, aimed at crippling British trade. The chapter analyzes the economic consequences of the blockade and its impact on European societies.

- Chapter 8: The Spanish Ulcer: Details the French intervention in Spain, the deposition of the Bourbon monarchy, and the outbreak of the Peninsular War. This chapter emphasizes the brutal nature of the conflict and the emergence of Spanish guerrilla warfare.

- Chapter 9: Wagram and the Austrian Marriage: Focuses on Napoleon's victory at the Battle of Wagram and his subsequent marriage to Marie Louise of Austria, solidifying his dynasty and forging an alliance with the Habsburg Empire. The chapter examines the political calculations behind the marriage and its impact on European diplomacy.

- Chapter 10: The Russian Gamble: Invasion and Retreat: Analyzes Napoleon's decision to invade Russia in 1812, exploring the strategic miscalculations and logistical challenges that led to the disastrous retreat from Moscow. This chapter highlights the devastating impact of the Russian winter and the destruction of the Grande Armée.

- Chapter 11: The War of Liberation: Leipzig and the Sixth Coalition: Describes the formation of the Sixth Coalition against Napoleon and the decisive Battle of Leipzig, also known as the Battle of Nations. The chapter analyzes the growing resistance to French rule across Europe and the shifting balance of power.

- Chapter 12: The Hundred Days: From Elba to Waterloo: Details Napoleon's escape from exile on Elba, his return to power in France, and the formation of the Seventh Coalition. This chapter emphasizes the political maneuvering and military preparations leading up to the Battle of Waterloo.

- Chapter 13: Waterloo: The Final Stand: Focuses on the Battle of Waterloo, analyzing the strategic decisions of Napoleon, Wellington, and Blücher, and the factors that contributed to Napoleon's final defeat. The chapter highlights the role of British resilience and Prussian intervention in securing victory for the Allies.

- Chapter 14: St. Helena: The Long Farewell: Examines Napoleon's final years in exile on St. Helena, exploring his reflections on his career and the legacy he left behind. The chapter analyzes the myths and legends surrounding Napoleon and their impact on historical memory.

- Chapter 15: The Congress of Vienna: Reordering Europe: Describes the Congress of Vienna, where European powers convened to redraw the map of Europe and restore the balance of power following Napoleon's defeat. The chapter analyzes the principles of legitimacy and compensation that guided the negotiations and the long-term consequences of the Congress.

- Chapter 16: Nationalism Unleashed: Seeds of Future Conflict: Explores the rise of nationalism as a powerful force in 19th-century Europe, tracing its roots to the Napoleonic era and its impact on subsequent conflicts. The chapter examines the emergence of national identities and the challenges of creating stable nation-states.

- Chapter 17: The Napoleonic Code: A Lasting Legacy: Evaluates the enduring influence of the Napoleonic Code on legal systems around the world, highlighting its impact on property rights, contract law, and civil liberties. The chapter analyzes the strengths and weaknesses of the Code and its continued relevance in the 21st century.

- Chapter 18: The Military Revolution: New Warfare, New World: Examines the impact of the Napoleonic Wars on military strategy and tactics, highlighting the rise of mass armies, the importance of logistics, and the development of new technologies. The chapter analyzes the evolution of warfare and its implications for future conflicts.

- Chapter 19: The Shadow Lingers: Napoleon in History and Memory: Explores the enduring fascination with Napoleon and his impact on historical memory, examining the different interpretations of his life and legacy. The chapter analyzes the myths and legends surrounding Napoleon and their role in shaping our understanding of the past.

- Chapter 20: A Balance Sheet of Ambition: The Napoleonic Era Assessed: A concluding chapter that provides a final assessment of the Napoleonic era, weighing the positive and negative consequences of Napoleon's reign and his impact on European and world history. It reinforces Blackwood's "historical triangulation" by presenting multiple viewpoints on Napoleon's legacy.

Chapter 1: The Inheritance of Revolution

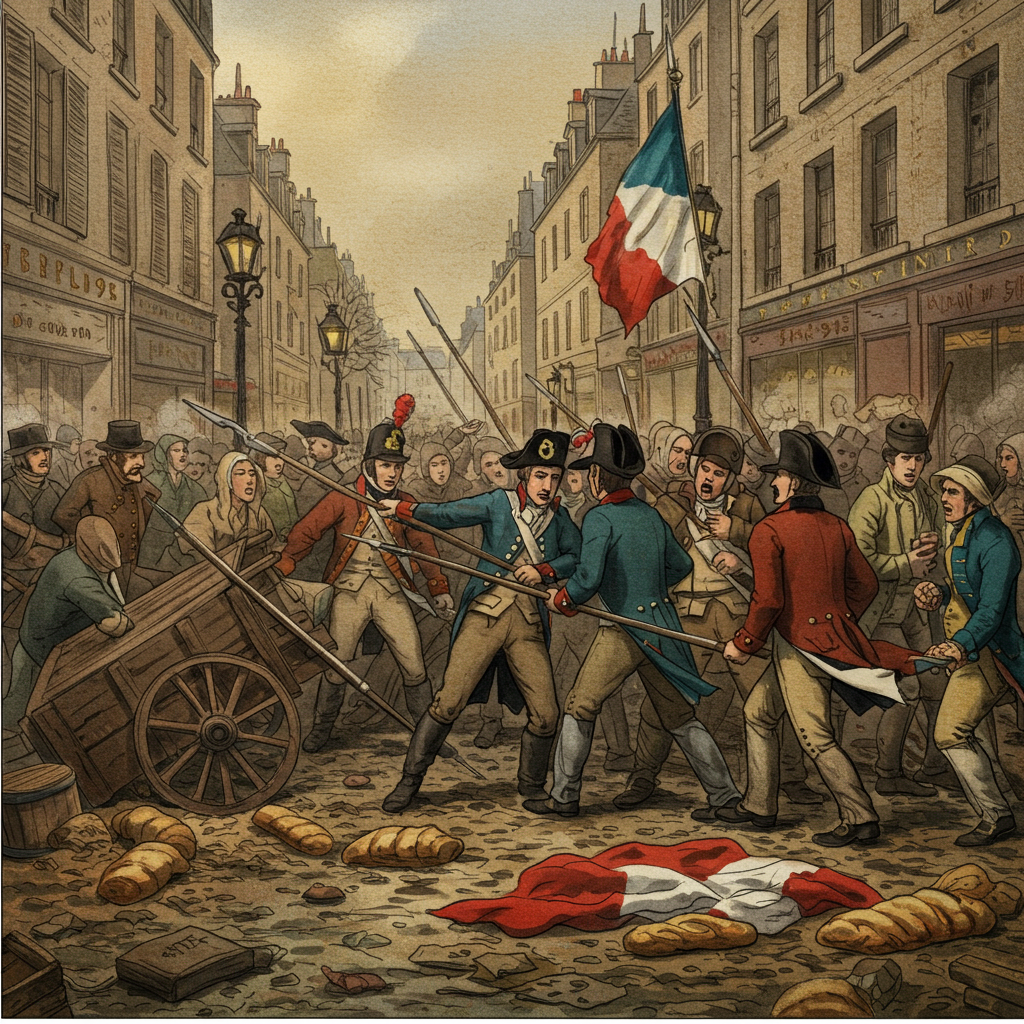

The year is 1799. Europe, a continent once defined by the stately cadence of dynastic succession and the seemingly immutable order of aristocratic privilege, now finds itself adrift in the turbulent wake of the French Revolution. The storm that had broken over France a decade prior had not merely subsided; rather, it had scattered its tempestuous seeds across the continent, germinating in the fertile soil of discontent and ideological ferment. The old certainties, once held as self-evident truths, were now questioned, challenged, and, in many cases, violently overthrown. To understand the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte, and the subsequent cataclysm of the Napoleonic Wars, one must first comprehend the fractured and febrile landscape he inherited.

The most immediate inheritance, of course, was the precarious state of the French Republic itself. The Directory, that five-man executive body ostensibly governing France, was a byword for corruption, incompetence, and political paralysis. A revolving door of factions vying for power, each more self-serving than the last, ensured a state of near-constant instability. The revolutionary fervor that had once propelled the nation forward had largely dissipated, replaced by a weary cynicism and a deep-seated yearning for stability. The ideals of liberté, égalité, fraternité had become tarnished by the excesses of the Terror and the subsequent self-enrichment of the Directory’s members. Economic woes compounded the political crisis. Rampant inflation, fueled by reckless printing of assignats (revolutionary currency), crippled the French economy. Public finances were in shambles, and the treasury teetered on the brink of bankruptcy. Bribery and embezzlement were rampant, further eroding public trust in the government. The armies of the Republic, though still formidable fighting forces, were often unpaid and ill-supplied, relying on plunder and requisition to sustain themselves. This, naturally, alienated the populations of the territories they occupied, sowing the seeds of future resistance.

Social unrest was endemic. The sans-culottes, the radical urban working class who had played such a crucial role in the Revolution, felt betrayed by the Directory's perceived abandonment of their interests. Bread riots and popular uprisings were commonplace, brutally suppressed by the Directory's military forces. In the countryside, Royalist insurgents, remnants of the old aristocracy and devout Catholics, continued to wage a guerrilla war against the Republic, particularly in the Vendée region. The chouannerie, as this counter-revolutionary movement was known, represented a persistent challenge to the Directory’s authority and a stark reminder of the deep divisions that still plagued French society. This internal strife, coupled with the external pressures of war against a coalition of European powers, created a perfect storm of instability. The Directory, lacking both the legitimacy and the competence to address these challenges, was rapidly losing control.

Beyond France, the shockwaves of the Revolution had reverberated throughout Europe, igniting a powder keg of ideological conflict. The established monarchies, terrified by the prospect of revolutionary contagion, had formed a series of coalitions to contain the spread of French influence and restore the Bourbon monarchy. Great Britain, driven by its strategic and commercial interests, emerged as the most consistent and implacable opponent of revolutionary France. Possessing the world's most powerful navy, Britain used its maritime dominance to blockade French ports, disrupt its trade, and support anti-French insurgents across the continent. Austria, ruled by the Habsburg Emperor, represented the traditional heartland of continental conservatism. Deeply invested in the preservation of the old order, Austria had repeatedly clashed with France in Italy and the Rhineland, seeking to maintain its territorial holdings and prevent the expansion of French influence in Central Europe.

Russia, under the enigmatic Tsar Paul I, remained a wildcard in the European power game. Initially opposed to the Revolution, Paul’s erratic behavior and growing admiration for Napoleon led him to withdraw from the Second Coalition, creating further divisions among the anti-French powers. The smaller states of Europe – Prussia, Spain, the Netherlands, and the various Italian principalities – were caught in the crossfire of these great power rivalries. Some, like Prussia, had been defeated and humiliated by France, forced to cede territory and accept French domination. Others, like Spain, were nominally allied with France but chafed under the constraints of the alliance and secretly harbored resentment towards their powerful neighbor. The Holy Roman Empire, a patchwork of hundreds of independent states nominally under the authority of the Habsburg Emperor, was teetering on the brink of collapse, its antiquated structures unable to withstand the forces of revolutionary change.

Ideologically, Europe was a battleground between the forces of conservatism and liberalism, tradition and revolution. The old aristocratic elites clung to their privileges and sought to restore the pre-revolutionary order, invoking the principles of divine right and social hierarchy. The emerging middle classes, inspired by the Enlightenment and the ideals of the French Revolution, sought greater political representation, economic freedom, and social equality. Nationalism, a relatively new and potent force, was beginning to stir in various parts of Europe, fueled by a sense of shared identity, language, and culture. This nascent nationalism could be harnessed to both support and resist French domination, depending on local circumstances and grievances.

In short, the Europe of 1799 was a continent in crisis. Political instability, social unrest, ideological conflict, and economic woes had created a vacuum of power and a yearning for strong leadership. The Directory, discredited and ineffective, was unable to provide the stability and direction that France, and indeed much of Europe, desperately needed. Into this chaotic landscape stepped Napoleon Bonaparte, a brilliant and ambitious young general who had already distinguished himself on the battlefields of Italy and Egypt. He possessed the charisma, the military prowess, and the political acumen to seize the moment and reshape the destiny of Europe. The stage was set for his dramatic entrance, and the shadow of the eagle was about to fall across the continent. But would this shadow bring order and enlightenment, or a new era of tyranny and war? Only time would tell, but the coming years would be marked by a level of conflict and transformation unseen since the fall of the Roman Empire. The inheritance of revolution, a poisoned chalice of both opportunity and peril, had been passed on, and Napoleon was poised to drink deeply from it.

The Inheritance of Revolution

Madame Recamier's Salon

Chapter 2: Brumaire and the Consulate

The Directory, as we have seen, was a vessel rapidly taking on water. By 1799, the yearning for stability, for order, had become a palpable force in French society. The revolutionary fervor, once a roaring conflagration, had dwindled to a flickering ember, choked by the ashes of corruption and disillusionment. Into this fraught atmosphere stepped General Napoleon Bonaparte, a figure already wreathed in the laurel of military success, a man seemingly destined to seize the reins of power. His return from the Egyptian campaign, though strategically questionable, was a masterstroke of theatrical timing. The public, weary of the Directory's ineptitude, greeted him as a savior, a beacon of hope amidst the gathering storm.

The coup of 18 Brumaire (November 9, 1799), was not a spontaneous uprising, but a carefully orchestrated act of political maneuvering, a ballet of calculated ambition. Napoleon, in alliance with Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès, a Director himself and a cunning political theorist, and his brother Lucien Bonaparte, then President of the Council of Five Hundred, carefully laid the groundwork. They exploited the widespread fear of a Jacobin resurgence – a manufactured panic, to be sure, but one that resonated with the propertied classes. The legislative councils were persuaded, under the guise of protecting them from this phantom threat, to relocate to the Château de Saint-Cloud, safely outside the volatile atmosphere of Paris.

This relocation was the crucial first step. At Saint-Cloud, away from the Parisian mob and surrounded by Bonaparte's loyal troops, the Councils were far more susceptible to pressure. The following day, 19 Brumaire, the coup unfolded in a scene of near-farcical chaos. Napoleon, never one to shy away from the dramatic, addressed the Council of Ancients, attempting to justify his actions. His speech, however, was rambling and unconvincing, betraying a certain nervousness that belied his reputation for unflappable confidence. He spoke of conspiracies, of threats to the Republic, but offered little in the way of concrete evidence. The Ancients, initially sympathetic, began to waver.

The Council of Five Hundred proved even more resistant. When Napoleon entered their chamber, he was met with a cacophony of shouts and insults. "Outlaw! Down with the dictator!" members cried, some even physically assaulting him. It was a moment of genuine peril. Had Napoleon faltered, had his nerve broken, the coup might well have collapsed then and there. It was Lucien Bonaparte, as President of the Council, who salvaged the situation. With remarkable presence of mind, he ordered the guards to clear the chamber, claiming that the Council was being terrorized by a faction of assassins.

This was the pretext the troops needed. Murat, and other loyal officers, quickly deployed Grenadiers into the Orangerie. Bayonets fixed, they advanced on the Council, driving the deputies before them. The scene must have been quite something: elected representatives of the nation, scrambling for safety, pursued by armed soldiers. The coup was complete, not through the force of reasoned argument or popular acclaim, but through the brute force of military might.

The events of Brumaire are often portrayed as a triumph of Napoleon's genius, a testament to his political acumen. However, a more nuanced analysis reveals a far more complex picture. The coup succeeded not solely due to Napoleon's brilliance, but also because of the Directory's utter failure, the widespread yearning for order, and the ruthlessness of his methods. The French people, exhausted by years of revolution and instability, were willing to trade liberty for security, even if that security came at the price of authoritarian rule.

In the aftermath of Brumaire, the Directory was abolished, replaced by the Consulate, a triumvirate consisting of Napoleon, Sieyès, and Roger Ducos. However, it was clear from the outset that Napoleon was the dominant figure. Sieyès, with his elaborate constitutional theories, soon found himself outmaneuvered by the General's pragmatism and ambition. Ducos was a mere cipher, a loyal follower of Napoleon.

The Constitution of Year VIII, drafted under Napoleon’s direction, solidified his power. While it retained the façade of republican institutions – a Tribunate, a Legislative Body, a Senate – real authority resided in the hands of the First Consul, Napoleon Bonaparte. He controlled the executive branch, initiated legislation, appointed officials, and commanded the military. The other Consuls were little more than advisors, their influence strictly limited.

The plebiscite held to ratify the Constitution was a carefully managed affair. While the official results showed overwhelming support for the new regime, the process was marred by irregularities and manipulation. Opposition voices were silenced, and the vote was presented as a choice between Napoleon and chaos. Faced with such a stark alternative, the French people overwhelmingly endorsed the Constitution, effectively legitimizing Napoleon’s seizure of power.

The establishment of the Consulate marked a significant turning point in French history. It brought an end to the revolutionary period, ushering in an era of centralized authority, military expansion, and social consolidation. Napoleon, as First Consul, embarked on a series of reforms designed to restore order, revive the economy, and rebuild French society. The establishment of the Banque de France, the Concordat with the Catholic Church, and the promulgation of the Napoleonic Code were all hallmarks of this period.

These reforms, while undoubtedly beneficial in many respects, also served to consolidate Napoleon’s power. The Banque de France provided him with the financial resources to wage war. The Concordat neutralized the powerful Catholic Church, transforming it into a pillar of support for his regime. The Napoleonic Code, while enshrining certain revolutionary principles, also reinforced patriarchal social structures and centralized legal authority.

Napoleon’s consolidation of power was not without its opponents. Royalists, Jacobins, and republicans all harbored resentment towards the new regime. However, Napoleon proved adept at suppressing dissent, utilizing a combination of repression, propaganda, and patronage to maintain control. He established a secret police, under the direction of Joseph Fouché, to monitor and neutralize his enemies. He controlled the press, ensuring that only favorable news reached the public. He lavished favors and honors on those who supported him, creating a loyal elite that owed its allegiance to him alone.

By 1802, Napoleon felt secure enough in his position to further consolidate his authority. Another plebiscite was held, this time to approve his appointment as Consul for Life. Again, the results were overwhelmingly in his favor, a testament to his popularity and his control over the political process. This marked a further step away from the ideals of the Revolution and towards the establishment of a personal dictatorship. The Republic, in all but name, was dead.

The Brumaire coup and the establishment of the Consulate represent a pivotal moment in the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte. It was a triumph of ambition, political maneuvering, and military force. It marked the end of the French Revolution and the beginning of a new era, one dominated by the figure of Napoleon. But even as Napoleon consolidated his power in France, storm clouds were gathering on the horizon. The peace of Amiens, signed in 1802, proved to be a fragile truce, and the underlying tensions between France and Great Britain were soon to erupt into renewed conflict, plunging Europe into another decade of war. The stage was set for the Emperor to make his entrance, but the seeds of his ultimate downfall were already sown in the very act of seizing power.

Emperor of the French

Trafalgar and Austerlitz: Sea and Land

Chapter 3: Marengo and the Peace of Amiens

The year 1800 dawned upon a Europe still scarred by the convulsions of revolution. While France, under the firm hand of First Consul Bonaparte, enjoyed a semblance of internal stability unseen for a decade, the war against the Second Coalition raged on. Austria, bolstered by British subsidies and driven by a deep-seated animosity towards revolutionary France, remained the primary obstacle to French dominance on the continent. The Italian peninsula, a patchwork of republics, kingdoms, and Austrian possessions, remained a key battleground. It was here, in the spring of 1800, that Napoleon would gamble everything on a campaign that would cement his authority and pave the way for a brief, illusory peace.

Napoleon's strategy was audacious, bordering on reckless. Leaving Moreau to confront the main Austrian army in Germany, Bonaparte would personally lead a reserve army across the Alps, aiming to strike at the Austrian rear in Italy. This was not merely a military maneuver; it was a calculated act of political theater. By emulating Hannibal's legendary crossing of the Alps, Napoleon sought to project an image of invincibility and daring, further solidifying his hold on the French imagination. The difficulties of the crossing, however, should not be understated. The army faced treacherous mountain passes, icy conditions, and the constant threat of avalanches. Artillery pieces had to be dismantled and hauled over the mountains by sheer manpower. Yet, the morale of the troops remained remarkably high, fueled by their faith in Bonaparte's leadership and the promise of glory.

The Austrian commander in Italy, General Melas, was caught completely off guard. He had anticipated a French offensive in Germany, not a daring thrust across the Alps. Napoleon's army descended upon the plains of Lombardy, disrupting Austrian supply lines and threatening their communications. Melas, initially dismissive of the threat, was forced to consolidate his forces and prepare for battle. The two armies finally clashed on June 14, 1800, near the village of Marengo.

The Battle of Marengo was a near-disaster for the French. Melas launched a strong attack, catching the French off balance. The French lines buckled, and the army began to retreat in disarray. By mid-afternoon, it seemed as though the battle was lost. However, Napoleon, displaying his characteristic resilience, rallied his troops and prepared for a desperate stand. The arrival of General Desaix's division in the late afternoon proved to be the turning point. Desaix, a highly capable and respected commander, launched a counterattack that checked the Austrian advance. Tragically, Desaix himself was killed in the assault, a loss that Napoleon deeply lamented.

The decisive moment of the battle came with a daring cavalry charge led by General Kellermann. Kellermann, acting on his own initiative, launched his heavy cavalry against the exposed Austrian flank, shattering their lines and throwing them into confusion. The Austrian army, exhausted and demoralized, began to retreat. The French victory at Marengo was secured, though at a heavy cost.

Marengo was more than just a military victory; it was a political triumph for Napoleon. The victory solidified his control over France and enhanced his prestige throughout Europe. Austria, facing mounting pressure on other fronts, was forced to sue for peace. The Treaty of Lunéville, signed in February 1801, confirmed French control over much of Italy and the Rhineland. With Austria defeated, only Great Britain remained at war with France.

The British, masters of the sea but unable to directly challenge French power on the continent, were increasingly isolated. The war had taken a heavy toll on the British economy, and public opinion was turning against the conflict. Negotiations between Britain and France began in the autumn of 1801, culminating in the Treaty of Amiens, signed in March 1802.

The Peace of Amiens, as it became known, was greeted with jubilation on both sides of the English Channel. After nearly a decade of war, Europe was finally at peace. However, the peace was fragile and short-lived. Underlying tensions remained unresolved. Britain refused to recognize French control over Belgium and the Netherlands, and Napoleon continued to meddle in European affairs, annexing Piedmont and exerting his influence over Switzerland.

Moreover, Napoleon's ambitions extended beyond Europe. He sought to restore French power in the Americas, sending an expedition to suppress the slave revolt in Saint-Domingue (modern-day Haiti). This expedition, however, ended in disaster, with the French army decimated by disease and the Haitian rebels ultimately achieving their independence. This failure, coupled with Napoleon’s sale of Louisiana to the United States, marked a turning point in French colonial ambitions.

The Peace of Amiens was, in essence, a truce, a temporary cessation of hostilities rather than a genuine reconciliation. Both sides viewed it with suspicion and distrust. Napoleon saw it as an opportunity to consolidate his power and rebuild his forces, while the British saw it as a breathing space before the inevitable resumption of the conflict. Indeed, within a year, the fragile peace would collapse, plunging Europe back into war and setting the stage for the epic struggles that would define the Napoleonic era. The underlying currents of ambition, rivalry, and ideological conflict, merely submerged beneath the surface of the Amiens treaty, were destined to resurface with renewed force. The shadow of the eagle, momentarily obscured, would soon darken the skies of Europe once more.

Marengo and the Peace of Amiens

Amiens, 1802

Chapter 4: Emperor of the French

The establishment of the French Empire in 1804 represents a pivotal, and some might argue, paradoxical moment in the unfolding drama of the Napoleonic era. It was, on the one hand, the seemingly inevitable culmination of Napoleon Bonaparte’s consolidation of power, a formal recognition of the de facto authority he already wielded. Yet, on the other hand, it marked a significant departure from the revolutionary ideals that had initially propelled him to prominence, a step towards the very ancien régime he had ostensibly overthrown. To understand this seemingly contradictory move, we must delve into the complex motivations that drove Napoleon’s decision and examine its profound implications for the delicate balance of power in Europe.

The official justification, promulgated by Napoleon and his supporters, was that the establishment of a hereditary empire would provide France with the stability and security it desperately needed after years of revolution and war. A republic, it was argued, was inherently unstable, prone to factionalism and vulnerable to external threats. A strong, hereditary ruler, on the other hand, could provide continuity and ensure the long-term interests of the nation. This argument resonated with a population weary of upheaval and yearning for order. The French Revolution, with its excesses and its instability, had arguably discredited the very notion of republicanism in the eyes of many. The yearning for a strong hand at the helm, a leader capable of navigating the treacherous waters of European politics, was a palpable force in French society.

However, there were undoubtedly more personal and pragmatic considerations at play. Napoleon, despite his undeniable popularity, remained vulnerable to assassination and conspiracy. As First Consul, his position was precarious, dependent on his continued success and the goodwill of the legislature. By transforming the Consulate into a hereditary empire, Napoleon sought to secure his dynasty and ensure the succession of his chosen heir. This was not merely an act of personal ambition; it was, in his view, a necessary step to safeguard the gains of the Revolution and prevent a return to the Bourbon monarchy. Moreover, the of Emperor carried with it a certain cachet, a symbolic weight that resonated with the traditions of European royalty. It elevated Napoleon above the level of a mere revolutionary leader, placing him on par with the emperors of Austria and Russia, and the kings of Prussia and Great Britain.

The coronation ceremony, held at Notre Dame Cathedral on December 2, 1804, was a carefully orchestrated spectacle designed to impress both domestic and foreign audiences. Pope Pius VII, summoned from Rome to preside over the event, was relegated to a secondary role as Napoleon famously crowned himself, a symbolic assertion of his own authority and independence from the Church. The lavish ceremony, replete with imperial regalia and military pomp, served to legitimize Napoleon’s rule in the eyes of the French people and the European aristocracy. It was a masterful display of political theater, designed to project an image of power, stability, and grandeur.

The implications of Napoleon’s self-coronation were far-reaching. It signaled a definitive break with the revolutionary past and a return to the principles of hereditary monarchy. It also fundamentally altered the balance of power in Europe, challenging the legitimacy of the existing monarchies and provoking widespread anxiety among European rulers. Great Britain, already wary of French expansionism, viewed Napoleon’s assumption of the imperial as a direct threat to its own interests and a clear indication of his insatiable ambition. The British government, under the astute leadership of William Pitt the Younger, worked tirelessly to forge a new coalition against France, uniting Austria, Russia, and other European powers in a common cause.

Alistair would note, with a certain academic detachment, that contemporary observers viewed the event with varying degrees of skepticism and alarm. In Britain, caricaturists lampooned Napoleon's coronation, depicting him as a power-hungry upstart grasping for legitimacy. In Vienna, the Habsburg Emperor Francis II regarded Napoleon's elevation with barely concealed disdain, seeing it as a challenge to the ancient authority of the Holy Roman Empire. Tsar Alexander I of Russia, initially intrigued by Napoleon, grew increasingly wary of his ambition and his disregard for traditional European norms. Even within France, there were those who questioned the wisdom of Napoleon's decision, fearing that it would lead to further conflict and undermine the revolutionary ideals they still cherished.

Alongside the establishment of the Empire, and inextricably linked to it, was the promulgation of the Napoleonic Code. Officially known as the Code Civil des Français, this comprehensive legal code represented one of Napoleon’s most enduring legacies. While often overshadowed by his military exploits, the Code had a profound and lasting impact on legal systems throughout Europe and beyond. It codified many of the principles of the French Revolution, including equality before the law, the abolition of feudalism, and the protection of property rights. It also established a uniform system of law, replacing the patchwork of regional customs and legal traditions that had prevailed in France prior to the Revolution.

The Napoleonic Code was not merely a codification of existing laws; it was a deliberate attempt to create a rational and coherent legal system based on Enlightenment principles. It emphasized clarity, simplicity, and accessibility, making it easier for citizens to understand their rights and obligations. It enshrined the principles of individual liberty, freedom of contract, and the sanctity of private property. It also established a secular legal system, separating law from religious dogma and asserting the authority of the state in matters of justice.

The impact of the Napoleonic Code extended far beyond the borders of France. As Napoleon’s armies conquered and occupied much of Europe, the Code was introduced into many of the newly conquered territories. In countries like Italy, Spain, and the Netherlands, the Code served as a model for legal reform, inspiring the adoption of similar legal systems. Even in countries that resisted French domination, the principles of the Napoleonic Code had a lasting influence on legal thinking and practice.

However, the Code was not without its critics. Some argued that it was overly centralized and authoritarian, reflecting Napoleon’s own autocratic tendencies. Others criticized its emphasis on property rights, arguing that it favored the wealthy and privileged at the expense of the poor and disadvantaged. Still others pointed to its patriarchal provisions, which granted men significant authority over women and children.

Despite these criticisms, the Napoleonic Code remains a landmark achievement in legal history. It represents a significant step towards the creation of a more just and equitable legal system, based on the principles of reason, equality, and individual liberty. Its enduring influence can be seen in the legal systems of many countries around the world, a testament to its enduring relevance and its transformative impact on European society.

The year 1804, therefore, stands as a watershed in the Napoleonic narrative. The self-coronation and the promulgation of the Code Civil represent two sides of the same coin: the consolidation of Napoleon's personal power and the institutionalization of revolutionary principles within a framework of imperial ambition. But the Emperor's actions had consequences. The die was cast. The crowned eagle had taken flight, its shadow stretching across the continent, a shadow that would soon darken into the long night of renewed war. And as the crowned heads of Europe looked on with growing trepidation, Pitt and his diplomats were already whispering in the shadows, forging the alliances that would eventually bring the Emperor to his knees. The stage was set for a new act in the drama, a conflict that would engulf Europe in flames and determine the fate of nations. The next chapter will examine the naval chess match between France and Great Britain, and the devastating battle of Trafalgar.

Emperor of the French

Chapter 5: Trafalgar and Austerlitz: Sea and Land

The year 1805 stands as a stark testament to the duality of Napoleon Bonaparte's ambition and the inherent limitations of his reach. It was a year of both unparalleled triumph and crushing defeat, a year that simultaneously cemented his dominance over continental Europe and definitively curtailed his aspirations for maritime supremacy. The battles of Trafalgar and Austerlitz, fought within a mere two months of each other, serve as potent symbols of this dichotomy, illustrating the enduring power of British naval might and the seemingly unstoppable force of the Grande Armée on land.

The Battle of Trafalgar, fought on October 21, 1805, off the coast of Spain, represents a pivotal moment in the Napoleonic Wars, though one curiously absent from the triumphal narrative carefully cultivated by Bonaparte himself. While Napoleon's propaganda machine relentlessly trumpeted his land victories, Trafalgar remained a muted subject, a shadow lurking behind the sun of Austerlitz. This reticence, however, does not diminish its significance. Indeed, Trafalgar ensured that Napoleon’s vision of a cross-channel invasion of England, a threat that had loomed large for years, would forever remain a strategic impossibility. The destruction of the Franco-Spanish fleet at the hands of Admiral Lord Nelson secured British naval supremacy for the remainder of the Napoleonic era and, arguably, for much of the 19th century.

Nelson's victory was not merely a matter of superior seamanship or tactical brilliance, though both were undoubtedly present. It was, in essence, a triumph of British maritime strategy, a culmination of decades of investment in naval infrastructure, training, and technology. The Royal Navy, unlike its continental counterparts, had evolved into a highly professional and disciplined force, capable of sustaining long-range operations and consistently outmaneuvering its adversaries. Furthermore, Nelson's innovative tactics, breaking the conventional line of battle to engage the enemy at close quarters, proved devastatingly effective. His famous signal, "England expects that every man will do his duty," encapsulated the spirit of patriotic fervor that infused the British fleet. Although Nelson himself perished in the battle, his sacrifice only served to further galvanize British resolve and cement his status as a national hero.

The consequences of Trafalgar extended far beyond the immediate tactical victory. The destruction of the Franco-Spanish fleet effectively neutralized Napoleon's ability to project power across the English Channel, thus removing the threat of invasion that had preoccupied the British government for years. This, in turn, allowed Britain to focus its resources on other fronts, particularly the Peninsular War, where Wellington would eventually prove to be Napoleon's most formidable adversary. Moreover, Trafalgar solidified Britain's control of the seas, enabling it to maintain its global trade networks and exert economic pressure on France through blockades and embargoes. The Continental System, Napoleon's attempt to strangle British commerce, would ultimately prove to be a self-inflicted wound, as it disrupted European economies and fueled resentment against French domination. As Alistair is want to remind his students, the freedom of the seas is the freedom to control the world’s economy. Without it, Napoleon’s aspirations were always land-locked.

While Trafalgar represented a strategic setback for Napoleon, the Battle of Austerlitz, fought on December 2, 1805, in present-day Czech Republic, stands as perhaps his most brilliant tactical victory. In a masterpiece of deception and maneuver, Napoleon decisively defeated the combined forces of Austria and Russia, shattering the Third Coalition and solidifying his control over much of continental Europe. The battle, fought on the first anniversary of his coronation as Emperor, was a carefully orchestrated display of military prowess, designed to intimidate his enemies and impress his allies.

Napoleon's success at Austerlitz stemmed from his meticulous planning, his ability to anticipate his opponents' moves, and his unwavering confidence in his own abilities. He deliberately feigned weakness, luring the Austro-Russian forces into attacking his right flank, while secretly concentrating his forces for a decisive counterattack in the center. The attack, launched with devastating force, split the enemy lines and sent them reeling in disarray. The Allied retreat quickly turned into a rout, with thousands of soldiers drowning in the frozen lakes as they attempted to escape.

The victory at Austerlitz had profound political and strategic consequences. Austria, humiliated and demoralized, was forced to sign the Treaty of Pressburg, ceding territory and paying a heavy indemnity to France. The Holy Roman Empire, a venerable institution that had endured for over a thousand years, was formally dissolved, replaced by the Confederation of the Rhine, a French-dominated alliance of German states. Russia, though defeated, remained a formidable power, but Tsar Alexander I was forced to reassess his alliance with Austria and seek new avenues for resisting Napoleon's expansionism.

The contrasting outcomes of Trafalgar and Austerlitz highlight the fundamental dilemma facing Napoleon. While he possessed unparalleled military genius on land, his lack of naval power severely limited his strategic options. He could conquer much of continental Europe, but he could not defeat Great Britain, the island nation that stood as the primary obstacle to his ambitions. This inability to project power across the English Channel would ultimately prove to be his undoing, as it allowed Britain to continue to support his enemies, finance coalitions against him, and eventually, to orchestrate his downfall.

Alistair would pause here, perhaps adjusting his spectacles, and remind the reader that this is not simply a story of military victories and defeats. It is a story of competing empires, of shifting alliances, and of the enduring power of geography. Napoleon, despite his brilliance and his ambition, could not overcome the fundamental reality of Britain's naval supremacy. Trafalgar ensured that the shadow of the eagle, though vast and imposing on the continent, could never extend across the seas. Austerlitz, for all its glory, was ultimately a pyrrhic victory, a triumph that masked the inherent limitations of Napoleon's power.

It is tempting, perhaps, to view Trafalgar and Austerlitz as isolated events, distinct episodes in the larger narrative of the Napoleonic Wars. However, such a compartmentalized view obscures the complex interplay between these two battles and their profound impact on the course of European history. Trafalgar, by securing British naval supremacy, enabled Britain to pursue a strategy of economic warfare and to support anti-French resistance movements across the continent. Austerlitz, by solidifying French dominance on land, forced Napoleon's enemies to seek new strategies for resisting his expansionism, leading to the formation of new alliances and the escalation of the conflict.

Moreover, the contrasting outcomes of these two battles highlight the different strengths and weaknesses of the two primary antagonists in the Napoleonic Wars: Great Britain and France. Britain, with its superior naval power and its vast colonial empire, possessed the resources and the strategic flexibility to wage a long-term war of attrition against Napoleon. France, with its powerful army and its centralized government, was capable of achieving stunning military victories on land, but lacked the ability to decisively defeat its maritime rival. This fundamental imbalance of power would ultimately prove to be the decisive factor in the Napoleonic Wars, as Britain's economic and naval strength gradually eroded Napoleon's empire, leading to his eventual defeat.

Alistair would conclude, tapping his pen thoughtfully against his notes, that the year 1805 serves as a microcosm of the entire Napoleonic era, a period of both unprecedented achievement and ultimate failure. The battles of Trafalgar and Austerlitz, though seemingly disparate events, are inextricably linked, representing the two sides of Napoleon's ambition and the enduring power of geography and maritime dominance. As the sun set on the fields of Austerlitz, little did Napoleon know that the seeds of his eventual downfall had already been sown on the waters off Trafalgar. The eagle might soar over the land, but the trident of Britannia ruled the waves.

The coming year, 1806, would bring further triumphs for Napoleon, particularly in his subjugation of Prussia, but the strategic impasse remained. The Continental System, designed to cripple Britain, began to unravel, causing economic hardship and resentment throughout Europe. The seeds of rebellion were being sown, particularly in Spain, where French ambitions would soon be bogged down in a protracted and bloody conflict. The limitations of Napoleon's reach, so starkly illuminated by Trafalgar, would continue to haunt him, ultimately leading to his downfall. The question now was not if, but when, the combined forces of Europe would finally be able to break the chains of French dominance. And the answer, as Alistair is sure to explore in the next chapter, lay not on the fields of glory, but in the hidden corners of European resistance and the unwavering resolve of the British Empire.

Trafalgar and Austerlitz: Sea and Land

Austerlitz Sunset

Chapter 6: The Confederation of the Rhine and the Fall of Prussia

The year 1806 stands as a particularly stark illustration of the disruptive force that Napoleon Bonaparte had become in the European order. A scant few months after the sun of Austerlitz had seemingly cemented his continental dominance, the very foundations of the Holy Roman Empire, that venerable, if increasingly moribund, institution, crumbled, and Prussia, a kingdom forged in the crucible of military discipline, found itself brought low in a manner that few would have predicted. These events, far from being isolated incidents, were intrinsically linked, each feeding off the other in a chain reaction of political and military upheaval.

The Treaty of Pressburg, signed in the aftermath of Austerlitz, was more than a mere cessation of hostilities; it was a surgical incision into the body politic of the German lands. Austria, humbled and forced to cede territory, was effectively sidelined as the dominant power within the Holy Roman Empire. This created a vacuum, one that Napoleon was only too eager to fill. He understood, perhaps better than any other contemporary statesman, the strategic importance of the German states. Their central location, their economic potential, and their capacity to provide manpower for his armies made them a crucial component of his grand design for European hegemony.

Thus, in July 1806, under the thinly veiled auspices of French protection, the Confederation of the Rhine was born. This was not a spontaneous act of German unity, as some propagandists would later attempt to portray it. Rather, it was a carefully orchestrated creation of Napoleon, a collection of sixteen German states – Bavaria, Württemberg, Baden, Hesse-Darmstadt, and a host of smaller principalities – bound together in a military alliance under his "protection." The rulers of these states, many of whom had been elevated to kings by Napoleon, were, in reality, little more than vassals, their autonomy subservient to the dictates of Paris.

The implications of the Confederation of the Rhine were far-reaching. The Holy Roman Empire, already weakened by centuries of internal division and external pressures, was dealt a death blow. On August 6, 1806, Francis II, Habsburg Emperor of Austria, formally renounced the of Holy Roman Emperor, bringing to an end a political entity that had, in one form or another, existed for over eight centuries. This act, while seemingly symbolic, represented a profound shift in the European order. The old, fragmented, and often chaotic world of the Holy Roman Empire, with its myriad principalities, free cities, and ecclesiastical territories, was replaced by a new, more streamlined system dominated by France.

The creation of the Confederation of the Rhine and the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire sent shockwaves throughout Europe, but nowhere was the reaction more pronounced than in Prussia. The Kingdom of Prussia, forged by the Great Elector and refined by Frederick the Great, had long considered itself the natural leader of the Protestant states of northern Germany. Its army, renowned for its discipline and its adherence to the rigid doctrines of Frederick, was widely regarded as one of the finest in Europe. Yet, for years, Prussia had vacillated between neutrality and tentative alliances with France, a policy driven by a mixture of caution, self-interest, and a profound miscalculation of Napoleon's true ambitions.

King Frederick William III, a well-meaning but indecisive ruler, found himself caught between conflicting pressures. On one hand, he was urged by his hawkish advisors, particularly Queen Louise, to assert Prussia's rightful place as a great power and to resist French encroachment. On the other hand, he was wary of provoking Napoleon, whose military prowess had been so demonstrably displayed at Austerlitz.

The formation of the Confederation of the Rhine proved to be the catalyst that finally pushed Prussia towards war. Frederick William, belatedly realizing the extent of Napoleon's ambition, issued an ultimatum demanding the dissolution of the Confederation and the withdrawal of French troops from German territory. This was a bold, perhaps even reckless, move, driven as much by wounded pride as by strategic calculation. Napoleon, never one to back down from a challenge, swiftly accepted the gauntlet.

The ensuing campaign was a disaster for Prussia. The Prussian army, clinging to outdated tactics and hampered by indecisive leadership, proved to be no match for the Grande Armée. On October 14, 1806, at the twin battles of Jena and Auerstedt, the Prussian forces were decisively defeated. At Jena, Napoleon himself led his troops to victory against a Prussian army commanded by the Prince of Hohenlohe. At Auerstedt, Marshal Davout, with a smaller force, inflicted a crushing defeat on the main Prussian army under the Duke of Brunswick.

The scale of the Prussian defeat was staggering. The army, once the pride of Europe, was shattered, its morale broken, and its leadership discredited. Fortresses fell like dominoes, and within weeks, French troops occupied Berlin, the Prussian capital. Frederick William III and Queen Louise were forced to flee to the easternmost reaches of their kingdom, seeking refuge in East Prussia under the protection of Tsar Alexander I of Russia.

The battles of Jena and Auerstedt marked not only the military defeat of Prussia but also the collapse of its political and social order. The old Prussian system, based on aristocratic privilege, rigid social hierarchies, and a powerful military bureaucracy, was exposed as brittle and outdated. The defeat revealed deep-seated weaknesses in the Prussian state, including a lack of effective leadership, a rigid adherence to outdated military doctrines, and a failure to adapt to the changing realities of European warfare.

Napoleon, triumphant in victory, imposed harsh terms on Prussia. The Treaty of Tilsit, signed in July 1807, stripped Prussia of nearly half its territory, including all its lands west of the Elbe River. These territories were used to create the Kingdom of Westphalia, ruled by Napoleon's brother Jérôme. Prussia was also forced to pay a hefty indemnity, to limit its army to a mere 42,000 men, and to join the Continental System, crippling its economy.

The fall of Prussia was a pivotal moment in the Napoleonic Wars. It demonstrated the overwhelming power of Napoleon's military machine and the vulnerability of even the most established European powers. It also marked the beginning of a period of profound reform and national awakening in Prussia, as figures like Stein and Hardenberg sought to modernize the state and to instill a new sense of national purpose in the Prussian people. The seeds of future resistance to French domination were sown in the very depths of this defeat. But that is a story for another chapter, for even in the face of such devastation, the spirit of Prussia, though wounded, was far from broken. The coming years would see the rise of a new Prussia, forged in the fires of adversity, one that would ultimately play a crucial role in Napoleon's downfall. And what role might Tsar Alexander play in Prussia's rise?

The Confederation of the Rhine and the Fall of Prussia

Jena-Auerstedt Aftermath

Chapter 7: Tilsit and the Continental System

The sun, it is said, never set on the British Empire. Yet, in the summer of 1807, it cast a long and ominous shadow indeed, one stretching across the continent of Europe, a shadow cast by the ascendant power of Napoleon Bonaparte. The twin treaties signed at Tilsit, a small town on the banks of the Neman River, marked not only the culmination of Napoleon's military triumphs over the Fourth Coalition, but also the apogee of his continental dominance. These agreements, however, represented far more than mere territorial adjustments; they were the cornerstone of a new European order, one predicated on the exclusion of Great Britain and the establishment of a French-dominated economic system known as the Continental System.

The preceding months had witnessed a series of events that dramatically reshaped the European landscape. The crushing defeats inflicted upon Prussia at Jena-Auerstedt in October 1806 had exposed the hollowness of its once-vaunted military reputation. Russia, despite its vast size and considerable military strength, had also suffered significant setbacks, most notably at the bloody but indecisive Battle of Eylau in February 1807 and the decisive French victory at Friedland in June. Tsar Alexander I, increasingly disillusioned with his allies and swayed by the allure of Napoleon's charisma, sought a path to peace, a path that would ultimately lead him to the negotiating table at Tilsit.

The meetings between Napoleon and Alexander were a carefully orchestrated display of diplomatic theater. The two emperors, both young, ambitious, and possessed of considerable personal magnetism, engaged in a series of private conversations, cultivating a sense of mutual respect and shared destiny. Napoleon, ever the master of manipulation, skillfully played upon Alexander's vanity and his desire for recognition on the European stage. He offered Russia territorial gains at the expense of Sweden and the Ottoman Empire, enticing Alexander with the prospect of expanding Russian influence in Eastern Europe.

The Treaty of Tilsit, signed on July 7, 1807, between France and Russia, formally established an alliance between the two powers. Russia agreed to join the Continental System, closing its ports to British trade and effectively declaring war on Great Britain. In return, Napoleon recognized Russia's interests in Eastern Europe and promised to support its expansionist ambitions. A second treaty, signed two days later between France and Prussia, was far more punitive. Prussia was stripped of vast swathes of territory, including all lands west of the Elbe River, which were incorporated into the newly created Kingdom of Westphalia, ruled by Napoleon's brother Jérôme. Prussia was also forced to pay a hefty indemnity to France and to reduce its army to a mere 42,000 men, effectively transforming it into a second-rate power. As Clausewitz later wrote, these treaties were not a peace, but merely an armistice, where Prussia was occupied by a foreign force and had to pay for it.

The implementation of the Continental System, however, proved to be a far more complex and challenging undertaking than Napoleon had initially anticipated. The aim was simple: to economically isolate Great Britain, depriving it of access to European markets and crippling its trade. By cutting off British exports, Napoleon hoped to undermine the British economy, weaken its financial system, and ultimately force it to sue for peace on his terms. The Berlin Decree of 1806 had already declared a blockade of the British Isles, prohibiting all trade with Britain and ordering the seizure of British goods. The Treaties of Tilsit extended this blockade to include Russia, Prussia, and a host of other European states under French control.

The economic consequences of the Continental System were far-reaching and unevenly distributed across Europe. British trade certainly suffered, particularly in the initial years of the blockade. British exports to Europe declined sharply, and British merchants faced increasing difficulties in finding markets for their goods. However, the British economy proved to be remarkably resilient. British merchants circumvented the blockade through smuggling, developing new trade routes to South America and Asia, and exploiting loopholes in the system. Furthermore, the British navy, which controlled the seas, was able to impose its own counter-blockade on French and European ports, further disrupting trade and exacerbating economic hardship on the continent. As a result, some of the intended effects of the Continental System were reversed.

The impact of the Continental System on European societies was equally complex and varied. Some regions, particularly those with close ties to British trade, suffered significant economic hardship. Ports such as Hamburg and Amsterdam, which had thrived on international commerce, experienced a sharp decline in activity, leading to unemployment and social unrest. Other regions, particularly those that benefited from increased industrial production or access to new markets, experienced a period of economic growth. The textile industry in Saxony, for example, flourished as it gained access to new markets in Eastern Europe, previously dominated by British manufacturers.

The Continental System also had a significant impact on European politics and social attitudes. It fostered resentment towards French domination and fueled the growth of nationalist sentiment in many parts of Europe. Smuggling became a widespread activity, undermining respect for law and order and contributing to a general sense of moral decay. The system also created opportunities for corruption and profiteering, as officials and merchants alike sought to exploit loopholes and evade the blockade. In short, it created a new class of nouveaux riches who got rich by gaming the system, whilst others who'd previously made their living through legitimate means were rendered destitute.

The implementation of the Continental System also placed a considerable strain on the Franco-Russian alliance. Alexander I, despite his initial enthusiasm for the alliance, soon found himself facing growing opposition from within his own court and among the Russian aristocracy, many of whom were heavily dependent on trade with Great Britain. Furthermore, the economic hardship caused by the blockade fueled discontent among the Russian population, leading to social unrest and political instability. The tensions between France and Russia gradually escalated, ultimately culminating in Napoleon's disastrous invasion of Russia in 1812, a campaign that would mark the beginning of the end for his empire.

The Treaties of Tilsit and the Continental System, therefore, represent a pivotal moment in the Napoleonic era. They marked the zenith of Napoleon's power, but also sowed the seeds of his ultimate downfall. The attempt to economically isolate Great Britain proved to be a costly and ultimately futile endeavor, undermining the French economy, fostering resentment across Europe, and contributing to the disintegration of the Franco-Russian alliance. The shadow of the eagle, it seemed, had stretched too far, casting a darkness that would ultimately engulf its creator.

But even as the Continental System faltered, a new resistance was brewing. The embers of Spanish defiance, fanned by British gold and Wellington's strategic brilliance, were about to ignite a conflagration that would tie down Napoleon's finest troops and bleed France dry. The Iberian Peninsula, previously a seemingly insignificant backwater, was about to become the stage for a protracted and brutal conflict, one that would test the limits of Napoleon's power and expose the vulnerabilities of his empire. It is to this peninsular war we must now turn our attention.

British Smugglers

Chapter 8: The Spanish Ulcer

The Treaties of Tilsit, as we have seen, seemingly cemented Napoleon’s dominion over continental Europe. With Prussia humbled, Austria cowed, and Russia allied, or at least ostensibly so, the Emperor of the French appeared to hold the destiny of the continent in his hand. Yet, beneath the veneer of French supremacy, fault lines were already appearing, tremors that would soon erupt into a protracted and bloody conflict, one that would drain Napoleon’s resources, erode his prestige, and ultimately contribute to his downfall: the Peninsular War.

The Iberian Peninsula, a land of proud traditions, fierce independence, and deep-seated religious conviction, proved to be a far more intractable problem than Napoleon initially anticipated. The kingdom of Spain, nominally an ally of France, was in reality a state riddled with internal divisions and governed by a weak and vacillating monarchy. King Charles IV, a man of limited intellect and even less political acumen, was dominated by his ambitious and unscrupulous wife, Queen Maria Luisa, and her paramour, Manuel Godoy, the Prime Minister. Godoy, a man of humble origins who had risen to power through the Queen's favor, pursued a policy of appeasement towards France, hoping to preserve his own position and enrich himself in the process.

Napoleon, ever the opportunist, saw Spain as both a strategic asset and a potential liability. Spain's control over key ports and its colonial possessions in the Americas made it a valuable ally in his ongoing struggle against Great Britain. However, Spain’s weakness and instability also made it vulnerable to British influence, a prospect that Napoleon could not tolerate. He therefore resolved to intervene directly in Spanish affairs, aiming to bring the country firmly under French control.

The pretext for French intervention was the ongoing war with Portugal, a long-standing ally of Great Britain. In 1807, Napoleon secured Godoy’s agreement to allow French troops to cross Spanish territory to invade Portugal. Under the terms of the Treaty of Fontainebleau, Portugal was to be partitioned, with Godoy receiving a portion of the spoils. However, Napoleon’s true intentions were far more ambitious. As French troops poured into Spain, ostensibly to support the invasion of Portugal, they began to occupy key cities and fortresses, effectively turning Spain into a French protectorate.

The Spanish people, already resentful of Godoy’s corrupt and pro-French policies, grew increasingly alarmed by the presence of French troops on their soil. Opposition to Godoy and the monarchy coalesced around Ferdinand, the Prince of Asturias, Charles IV's son. Ferdinand, a young and ambitious man, saw an opportunity to seize power and rid Spain of French influence. In March 1808, a popular uprising, known as the Mutiny of Aranjuez, forced Charles IV to abdicate in favor of Ferdinand. Godoy was arrested and imprisoned, and Ferdinand VII was proclaimed King of Spain.

However, Napoleon refused to recognize Ferdinand’s claim to the throne. He lured Ferdinand and Charles to Bayonne, a town in southwestern France, where he pressured them both to abdicate. In a humiliating display of dynastic intrigue, Napoleon forced both father and son to renounce their claims to the Spanish crown. He then installed his own brother, Joseph Bonaparte, as King of Spain.

The imposition of Joseph Bonaparte as King of Spain proved to be a disastrous miscalculation. The Spanish people, fiercely proud and deeply Catholic, refused to accept a foreign ruler imposed upon them by force. On May 2, 1808, the people of Madrid rose up in revolt against the French occupation. The uprising was brutally suppressed by French troops, but it ignited a flame of resistance that would spread throughout Spain. This event, immortalized in Goya’s paintings, became a symbol of Spanish defiance against French tyranny.

The Spanish War of Independence, or the Peninsular War as it became known, was a brutal and protracted conflict that lasted for six years. It pitted the French army, initially under the command of Marshal Murat and later under other experienced commanders, against a combination of Spanish regular forces, British troops under the command of Sir Arthur Wellesley (later the Duke of Wellington), and, most importantly, Spanish guerrilleros.

The guerrilleros, irregular fighters drawn from all levels of Spanish society, proved to be a formidable enemy. Operating in small, mobile bands, they harassed French troops, ambushed convoys, and disrupted supply lines. They were masters of the terrain, intimately familiar with the mountains, forests, and villages of Spain. The guerrilleros were often brutal in their methods, but they were also highly effective in tying down large numbers of French troops and preventing them from consolidating their control over the country. As Dr. Blackwood has often stated, this was the very beginning of the end for the French.

The Peninsular War quickly became a quagmire for Napoleon. The French army, accustomed to decisive battles and swift victories, found itself bogged down in a seemingly endless series of skirmishes, sieges, and ambushes. The logistical challenges of supplying a large army in a hostile and mountainous country proved immense. The French were forced to rely on foraging and requisitioning, which further alienated the Spanish population and fueled the resistance.

The brutality of the war was appalling. Both sides committed atrocities, with French troops often retaliating against civilian populations for guerrillero attacks. The Spanish guerrilleros, in turn, showed little mercy to captured French soldiers. The war became a cycle of violence and reprisal, leaving a lasting scar on the Spanish psyche. The "Spanish Ulcer," as Napoleon himself termed it, became a constant drain on French resources, both material and human. It diverted troops and supplies from other theaters of war, weakening Napoleon's overall strategic position. The conflict revealed the limitations of Napoleon's military genius and the vulnerability of his empire to popular resistance.

The arrival of British troops under the command of Sir Arthur Wellesley added another dimension to the conflict. Wellesley, a skilled and experienced commander, quickly recognized the strategic importance of Portugal and established a strong defensive position in the country. From this base, he launched a series of campaigns into Spain, inflicting a number of defeats on the French army.

The Battle of Vimeiro in August 1808 marked Wellesley’s first significant victory against the French in the Peninsular War. This was followed by the Convention of Sintra, a controversial agreement that allowed the defeated French troops to be evacuated from Portugal with their arms and baggage. Although Wellesley was critical of the Convention, it effectively secured Portugal from French control and established a foothold for British intervention in Spain.

The Peninsular War also had a significant impact on the political landscape of Europe. It demonstrated the limits of Napoleon's power and inspired resistance movements in other countries. The war also strengthened the alliance between Great Britain and Spain, providing Britain with a valuable ally in its ongoing struggle against France. Furthermore, the focus on Spain weakened the French position elsewhere, allowing Austria to attempt another revolt and challenge French dominance in 1809.

The Peninsular War, then, was far more than just a sideshow in the Napoleonic Wars. It was a crucial turning point in the conflict, a slow bleed that weakened Napoleon’s empire and paved the way for his eventual defeat. The seeds of Napoleon’s downfall were sown not on the snow-covered plains of Russia, but in the sun-baked hills and valleys of Spain, where the fierce resistance of the Spanish people and the strategic brilliance of Wellington combined to create a wound that would never fully heal. As Wellington prepared for a new offensive into Spain, the French situation was becoming increasingly untenable, a situation exacerbated by events brewing far to the East. The Austrian eagle was stirring once more, and the continent held its breath, awaiting the next clash of empires.

Spanish Guerrillas

Chapter 9: Wagram and the Austrian Marriage

The year 1809, following the uneasy calm imposed by the Treaties of Tilsit, saw Europe once again plunged into the crucible of war. Austria, smarting from its previous defeats and emboldened by the ongoing struggles in Spain, perceived an opportunity to challenge Napoleonic dominance. Emperor Francis I, advised by the bellicose Archduke Charles, believed that a renewed Austrian effort, coupled with potential uprisings in Germany and a resurgent spirit of resistance, could finally break the French Emperor’s grip on the continent. This, of course, proved to be a grave miscalculation, born more of wishful thinking than a realistic assessment of the balance of power.

The Austrian campaign of 1809, while initially enjoying some success, ultimately demonstrated the enduring military genius of Napoleon Bonaparte. The Battle of Aspern-Essling, fought in May, presented the French Emperor with a rare tactical defeat, a bloody and costly affair that temporarily halted his advance on Vienna. However, Napoleon, ever resilient, regrouped his forces, learned from his mistakes, and prepared for a decisive confrontation.

That confrontation came at Wagram, a sprawling plain northeast of Vienna, in early July. The Battle of Wagram was a colossal affair, involving hundreds of thousands of troops and stretching over two days of intense fighting. The Austrian army, under the command of Archduke Charles, adopted a defensive posture, hoping to exploit the terrain and wear down the French through attrition. Napoleon, however, opted for a more aggressive strategy, seeking to break the Austrian lines and achieve a decisive victory.

The battle was characterized by fierce artillery duels, desperate infantry charges, and daring cavalry maneuvers. The French artillery, under the command of the skilled General Lauriston, played a crucial role in pounding the Austrian defenses. The Austrian infantry, known for their discipline and tenacity, put up a stubborn resistance, but ultimately proved unable to withstand the relentless French attacks.

Napoleon’s strategic brilliance was evident in his handling of the battle. He recognized the key weaknesses in the Austrian line and concentrated his forces to exploit them. He skillfully employed his reserves to reinforce threatened sectors and launch counterattacks. He also demonstrated a remarkable ability to inspire his troops, urging them forward despite heavy casualties. Dr. Blackwood has often noted that Napoleon's personal presence on the battlefield was worth several divisions. This day at Wagram was no exception.

After two days of grueling combat, the Battle of Wagram ended in a decisive French victory. The Austrian army, though not completely destroyed, was forced to retreat, its morale shattered. Emperor Francis I, realizing the futility of further resistance, sued for peace.

The Treaty of Schönbrunn, signed in October 1809, imposed harsh terms on Austria. Austria ceded territory to France, Bavaria, and Russia, further diminishing its power and influence. It also agreed to pay a substantial indemnity and to reduce its army to a minimum size. The 1809 campaign, therefore, resulted in Austria’s further subordination to French dominance.

However, the most significant consequence of the 1809 campaign was not territorial or financial, but rather dynastic. Napoleon, now approaching his forties, faced a pressing problem: he lacked an heir. His marriage to Joséphine de Beauharnais, while a love match in its early years, had failed to produce children. The need for a legitimate successor to secure the future of his empire became increasingly urgent.

Napoleon, ever pragmatic, resolved to divorce Joséphine and seek a new wife from one of Europe's royal houses. The choice ultimately fell upon Marie Louise, the daughter of Emperor Francis I of Austria. This decision, though politically astute, marked a significant departure from the revolutionary ideals that had initially propelled Napoleon to power. It signaled his embrace of traditional European power politics and his desire to be accepted as an equal by the old aristocratic elites.

The Austrian marriage was a carefully calculated move on both sides. For Napoleon, it provided the prospect of a legitimate heir and forged an alliance with one of Europe's major powers. For Austria, it offered a temporary respite from French aggression and a chance to regain some of its lost influence. The marriage was brokered by the wily Austrian diplomat Prince Metternich, who saw it as a means of stabilizing the European order, albeit under French hegemony.

The wedding of Napoleon and Marie Louise, held in Vienna in March 1810, was a lavish affair, a spectacle of imperial grandeur designed to impress the world with the power and prestige of the French Empire. The event was attended by dignitaries from across Europe, including representatives of Austria, Prussia, Russia, and the various German states. The marriage was widely hailed as a triumph of diplomacy and a symbol of peace and stability.

However, beneath the veneer of harmony, tensions remained. Many in Austria resented the marriage, viewing it as a humiliating submission to French dominance. Others in France questioned the wisdom of allying with the Habsburgs, the traditional enemies of the French Revolution. The marriage, therefore, was not without its critics and skeptics.

The arrival of a male heir, Napoleon Francis Joseph Charles Bonaparte, in March 1811, was greeted with jubilation throughout the French Empire. The birth of the King of Rome, as he was styled, seemed to secure the future of the Napoleonic dynasty and solidify Napoleon’s position as the undisputed master of Europe. But as Dr. Blackwood has often said, hubris is the seed of destruction. This sense of invincibility, born of victory at Wagram and cemented by the Austrian marriage, would soon lead Napoleon to make a series of fateful decisions that would ultimately lead to his downfall. The looming shadow of Russia, and the Tsar's growing unease with Napoleon’s dominance, threatened to unravel the fragile peace of Tilsit, promising a conflict far bloodier and more devastating than any Europe had yet witnessed. The stage was set for the cataclysm to come.

Wagram and the Austrian Marriage

Chapter 10: The Russian Gamble: Invasion and Retreat

The year 1812 stands as a stark, icy monument to the perils of hubris and the limitations of even the most formidable military machine. Napoleon Bonaparte, at the zenith of his power, having cowed or coerced most of continental Europe into submission, turned his gaze eastward, towards the vast, enigmatic expanse of Russia. This decision, as Dr. Blackwood has often argued in his lectures, was not born of strategic necessity, but rather of a peculiar blend of political pique, economic calculation, and, perhaps most significantly, a profound misjudgment of the Russian character and the realities of its geography.

The ostensible cause for the invasion was Tsar Alexander I’s increasingly lukewarm adherence to the Continental System, Napoleon’s economic blockade designed to strangle British trade. While Alexander had nominally agreed to the system at Tilsit in 1807, the economic hardship it imposed on Russia, particularly its landed aristocracy who relied on trade with Britain, led to a gradual relaxation of enforcement. Napoleon viewed this as a betrayal, a direct challenge to his authority and a threat to the overall effectiveness of the blockade. As Dr. Blackwood has noted in previous publications, "Napoleon often conflated economic policy with personal loyalty, viewing any deviation from his dictates as a personal affront."

Beyond economics, there was a deeper political dimension to the conflict. Napoleon, ever conscious of his own legitimacy as a parvenu emperor, sought to assert his dominance over all of Europe, including its eastern fringes. He viewed Alexander, despite their previous alliance, as an unreliable partner, susceptible to the influence of anti-French factions within the Russian court. A decisive military victory, Napoleon believed, would bring Alexander to heel and solidify French hegemony over the continent.