The Almost Kosher Configuration: A Rabbi's Guide to Emacs Enlightenment

The Almost Kosher Configuration: A Rabbi's Guide to Emacs Enlightenment

Synopsis

Rabbi Dr. Moishe "Moe" Perlstein, PhD (Emacs), a man torn between the ancient wisdom of Talmudic law and the seductive allure of customizable text editors, finds himself facing a crisis of faith – not in God, but in the default keybindings of Emacs. When a mysterious bug threatens to corrupt the synagogue's meticulously organized digital archive (powered, naturally, by Emacs Org mode), Moe embarks on a quest to create the ultimate Emacs configuration, a "foobar mistsvah" of coding and commandment-keeping.

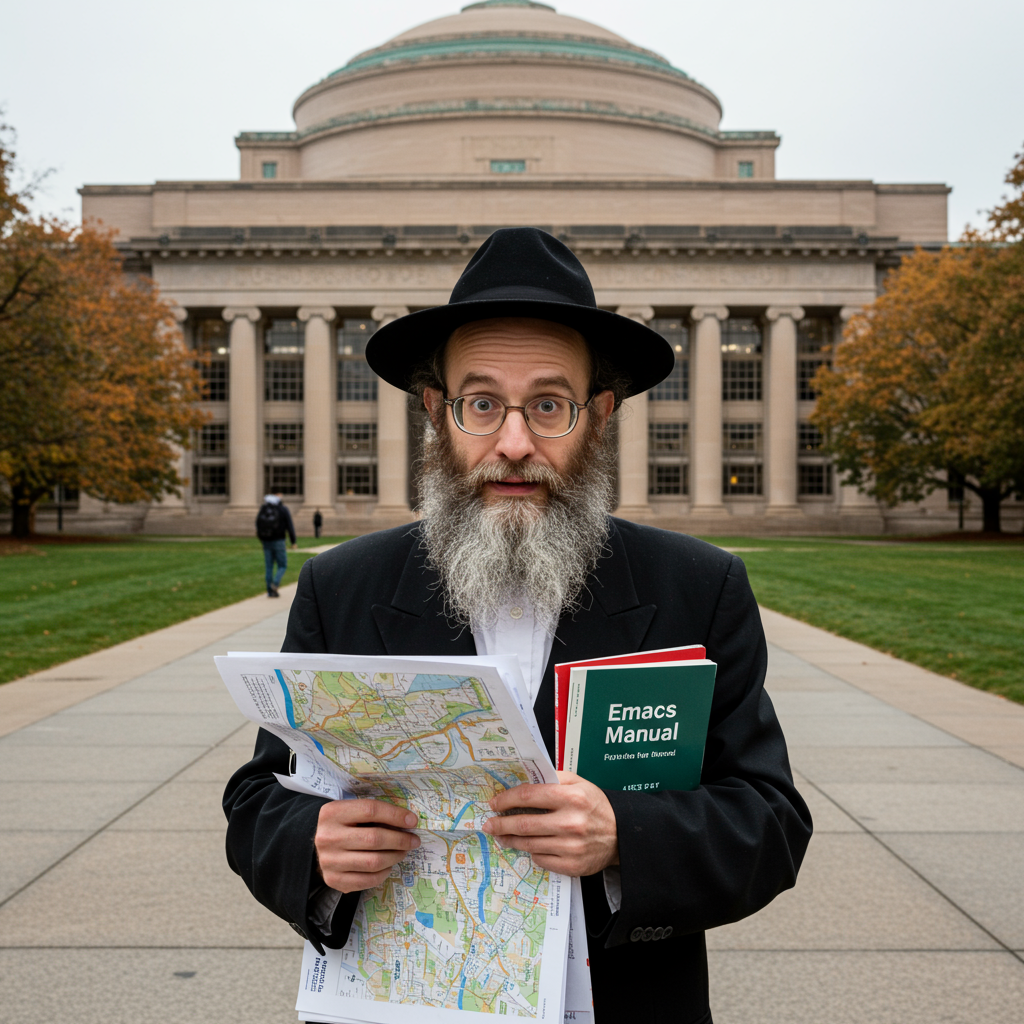

His journey takes him from the dimly lit corners of online Emacs communities to clandestine meetings with rogue Lisp programmers, and even a pilgrimage to the birthplace of Emacs itself, MIT. Along the way, he battles rival rabbis who prefer Vim (the "Amalekites" of the text editor world), wrestles with the ethical implications of AI-powered Halakha analysis, and confronts his own long-standing anxieties about the ever-accelerating pace of technological change.

"The Almost Kosher Configuration" is a hilarious and heartwarming exploration of faith, technology, and the enduring human need to find meaning in the most unexpected places. Through Moe's misadventures, readers will discover that sometimes, the most profound truths can be found not in ancient texts, but in the intricate, customizable depths of a well-configured Emacs buffer. And maybe, just maybe, learn a little Emacs Lisp along the way.

Table of Contents

- Chapter 1: The Curse of C-x C-c: Rabbi Moe Perlstein, PhD (Emacs), enjoys a perfectly calibrated morning routine – prayer, Talmud study, and, of course, the meticulous organization of his digital notes in Emacs. A mysterious bug emerges, corrupting files and threatening the synagogue's archive.

- Chapter 2: The Prophecy of the Init File: Moe consults with the synagogue’s resident computer whiz, a teenage prodigy named Shira, who diagnoses the issue: a corrupted Emacs initialization file. She speaks of a legendary "foobar mistsvah," a perfect Emacs configuration that can solve any problem.

- Chapter 3: The Vimite Heresy: A rival rabbi, Rabbi Lipschitz, a staunch advocate of Vim, arrives to gloat over Moe's misfortune. Their long-standing rivalry escalates as they debate the merits of different text editors, invoking ancient Talmudic arguments.

- Chapter 4: The Wisdom of the Online Elders: Moe ventures into the murky depths of online Emacs communities, seeking guidance from seasoned Lisp programmers. He encounters a cast of eccentric characters, each with their own idiosyncratic Emacs configurations and opinions.

- Chapter 5: The Secret of the .Emacs.d: Moe discovers a hidden message within an ancient .emacs.d directory, hinting at a secret society of Emacs gurus who hold the key to the "foobar mistsvah." The message leads him to a cryptic location: MIT.

- Chapter 6: The Pilgrimage to Cambridge: Moe travels to MIT, the birthplace of Emacs, hoping to find the secret society. He wanders through the hallowed halls of the AI lab, encountering eccentric professors and bewildered students.

- Chapter 7: The Confessions of the Lisp Hacker: Moe finally locates a former member of the secret society, a disillusioned Lisp hacker named Ezra. Ezra reveals the history of the society and the true nature of the "foobar mistsvah": a never-ending quest for perfection.

- Chapter 8: The Ritual of Customization: Ezra guides Moe through the complex rituals of Emacs customization, teaching him arcane Lisp commands and the importance of understanding the underlying principles of the editor.

- Chapter 9: The Temptation of AI Halakha: Moe becomes intrigued by the possibility of using AI to analyze Jewish law, but Ezra warns him against the dangers of relying too heavily on technology in matters of faith.

- Chapter 10: The Battle of the Keybindings: Rabbi Lipschitz challenges Moe to a keybinding duel, a public demonstration of their Emacs skills. The duel becomes a metaphor for the larger conflict between tradition and modernity.

- Chapter 11: The Overflowing Buffer: During the keybinding duel, the synagogue's archive system crashes again, this time due to a buffer overflow error. Moe realizes that the "foobar mistsvah" is not about achieving perfection, but about embracing imperfection.

- Chapter 12: The Almost Kosher Configuration: Moe uses his newly acquired Emacs skills to fix the buffer overflow, saving the synagogue's archive. He creates a customized Emacs configuration that is not perfect, but "almost kosher," reflecting the messy reality of life.

- Chapter 13: The Mitzvah of Maintenance: Moe realizes that the true "foobar mistsvah" is not a one-time accomplishment, but an ongoing commitment to maintaining and improving his Emacs configuration, just as he must maintain and improve his faith.

- Chapter 14: The Reunion of the Rabbis: Moe and Rabbi Lipschitz reconcile, realizing that their rivalry was ultimately a distraction from the common goal of serving their community. They agree to collaborate on a joint project: a website dedicated to Emacs-based Jewish resources.

- Chapter 15: The Legacy of the Init File: Moe reflects on his journey, realizing that the true value of Emacs is not its technical capabilities, but its ability to connect people and foster a sense of community. He decides to pass on his knowledge to the next generation, starting with Shira.

Chapter 1: The Curse of C-x C-c

The morning, as it often did in my little corner of Brooklyn, began with a battle. Not a loud, bombastic battle involving exploding bagels (though those have happened, believe you me), but a quiet, internal struggle between the sacred and the… well, the slightly less sacred, but equally demanding: Emacs.

It was 6:00 AM, precisely. My internal clock, calibrated more accurately than the atomic clocks at NIST (or so I liked to imagine), yanked me from the clutches of sleep. First, Mode-line be praised, Netilat Yadayim – the ritual washing of hands. One must approach the digital world with clean intentions, after all. Then, Shacharit, morning prayers. I find the rhythmic chanting, the ancient Hebrew words, surprisingly compatible with the click-clack symphony of my mechanical keyboard. Some rabbis scoff at the notion of integrating technology into prayer, but I say, nu, isn’t the digital world just another manifestation of God's creation, albeit one slightly more prone to buffer overflows?

Next, the daily dose of Talmud. Tractate Gitin, specifically, dealing with the intricacies of divorce law. Irony, perhaps, considering my deeply committed relationship with Emacs. You see, Emacs is like a marriage. You pour your heart and soul into it, customize it to your every whim, and occasionally, it betrays you with a cryptic error message at 3 AM. But you stick with it, because the potential rewards – the sheer, unadulterated power of a perfectly configured text editor – are too great to ignore.

And then, finally, the moment I’d been simultaneously anticipating and dreading: the organization of my digital notes. My entire rabbinical existence, nay, my very being, is meticulously cataloged and cross-referenced in Emacs Org mode. Sermons, Halakha rulings, shopping lists for cholent ingredients – all there, neatly organized and readily accessible with a strategically placed C-c C-o.

I fired up Emacs, the familiar green text on a black background a comforting sight. My .emacs.d directory, my digital mikvah, held centuries of accumulated wisdom, both ancient and modern. Each keystroke, each command, felt like a sacred act, a reaffirmation of my commitment to both tradition and technology.

But this morning, something was…off.

A faint tremor of unease ran through me as I navigated to my main notes file, rabbi.org. The cursor blinked mockingly, daring me to proceed. I took a deep breath, a technique I learned from my yoga instructor (another surprisingly compatible pursuit with Emacs – try doing a headstand while simultaneously remapping your Caps Lock key; it’s quite the experience).

And then, it happened.

As I attempted to open the file, a cascade of error messages erupted on the screen, a digital geyser of frustration and despair. Lines of Lisp code, incomprehensible to the uninitiated, scrolled past at alarming speed. The familiar Org mode interface dissolved into a chaotic jumble of characters.

My heart pounded in my chest. This wasn’t just a minor glitch. This was…a catastrophe.

I tried again. And again. Each attempt yielded the same horrifying result. My files, my precious files, were being… corrupted.

Panic threatened to overwhelm me, but I fought it back with the discipline of a seasoned debugger. Think, Moishe, think! What could have caused this? A rogue package? A corrupted cache? A solar flare interfering with the delicate balance of my motherboard?

Then, a chilling thought struck me, a thought so terrible it sent a shiver down my spine that had nothing to do with the Brooklyn chill. The Curse of C-x C-c.

It was just a legend, a whispered warning passed down through generations of Emacs users. The Curse of C-x C-c: the dreaded keybinding for “kill-emacs.” Legend had it that invoking this command at the wrong time, in the wrong state of mind, could unleash a malevolent force that would corrupt your files, scramble your configurations, and ultimately, drive you mad.

Nonsense, I told myself. Superstition. I’m a scientist, a rational human being (mostly). But the evidence was undeniable. The error messages, the corrupted files, the sheer, unmitigated wrongness of the situation… it all pointed to one conclusion: I had angered the Emacs gods.

And the synagogue’s archive… the entire digital record of our community’s history, from birth certificates to bar mitzvah speeches, all stored in meticulously organized Org files… it was all vulnerable.

The weight of responsibility crashed down on me. I had to fix this. I had to break the curse. But how?

Just then, the shrill ring of my phone shattered the silence. It was Mrs. Rosenblatt, the synagogue president.

“Rabbi Perlstein,” she said, her voice tight with anxiety, “we have a problem. A big problem. The records… they’re all messed up. I can’t find anything! Did you… did you do something to the computer?”

I swallowed hard. The curse was spreading.

“I’ll be right there, Mrs. Rosenblatt,” I said, my voice trembling slightly. “I’ll fix it. I promise.”

But as I hung up the phone, I couldn’t shake the feeling that I was facing something far more sinister than a simple software bug. This was a battle for the soul of my synagogue, a battle for the very essence of our community. And I, Rabbi Moe Perlstein, PhD (Emacs), was about to enter the digital fray, armed with nothing but my wits, my Lisp skills, and a growing sense of dread.

I glanced at the clock. 7:30 AM. Time to face the music, and perhaps, a full system restore. But first, a double shot of espresso. And maybe, just maybe, a quick prayer to the Emacs gods. It couldn't hurt, right?

As I reached for my coffee mug, I noticed something else amiss. My custom Emacs theme, “Midnight Dreidel,” had reverted to the default “Wanderlust.” A shiver ran down my spine. This wasn't just a curse; it was personal. Someone, or something, was messing with my configuration.

The battle had just begun.

But who? And why? The synagogue's resident computer whiz, Shira, was always helpful, but could she possibly have been the one to unleash this chaos? Or was there a darker force at play, a digital saboteur lurking in the shadows, intent on disrupting the harmony of our community? I considered my long standing rivalry with Rabbi Lipschitz, the Vimite Heretic, whose congregation had been in constant competition for the last 15 years.

The next chapter would tell, and as I considered the options, I felt a sense of purpose awaken within me. If I was to fix this, I had to start with the Init file.

The Morning Routine

C-x C-c Catastrophe

Chapter 2: The Prophecy of the Init File

The phone call with Mrs. Rosenblatt ended, as most of our interactions did, with a sigh – hers. Mine, internal, of course. One doesn't want to overtly display the burden of leadership, even when that burden feels like a particularly heavy shtreimel on a sweltering summer day.

"Rabbi," she'd concluded, "just… fix it, please. Before the Sisterhood starts using carrier pigeons to communicate. And could you maybe, you know, use a normal computer next time?"

Ah, "normal." A word fraught with peril. To a layperson, "normal" might mean a Windows machine, churning away with the efficiency of a caffeinated hamster on a wheel. But to me? To me, "normal" is the glorious, infinitely customizable, and occasionally maddening world of Emacs.

I slumped back in my ergonomic chair (another concession to modernity, though my bubbe would have preferred I sit on a pile of Talmud volumes for proper posture). The situation was dire. Not only was the synagogue's digital archive in peril, but my reputation – my carefully cultivated image as a rabbi who could debug a kernel panic while simultaneously delivering a sermon on the weekly Torah portion – was crumbling faster than a poorly-made rugelach.

There was only one thing to do. Consult the oracle. Not the mystical kind, mind you. We're not talking about tea leaves and tarot cards here. No, this was a digital oracle, a young woman with fingers that danced across the keyboard like a hummingbird on speed, a mind that could unravel the most complex Lisp code, and a hairstyle that changed color more often than the weather in New York. I speak, of course, of Shira.

Shira was the synagogue's resident computer whiz, a teenage prodigy who volunteered her time to keep our digital infrastructure from collapsing into a heap of binary rubble. She was also, bless her heart, the only person in the congregation who understood what I was talking about when I mentioned "buffer overflows" and "elisp macros."

I fished my phone out of my pocket – a decidedly un-Emacsian device, I'll admit, but necessary for navigating the analog world – and tapped out a text.

"Shira, urgent. Digital emergency at the synagogue. Think Curse of C-x C-c. Can you come ASAP? Pizza involved."

The response was instantaneous: "Be there in 10. Extra cheese?"

Ten minutes later, Shira burst through the door of my study, a whirlwind of electric blue hair, Doc Martens, and nervous energy. She was carrying her trusty laptop bag, which I suspected contained more debugging tools than the entire IT department at Goldman Sachs.

"Rabbi Moe!" she exclaimed, her voice a mixture of concern and excitement. "What's the sitch? The archive? Is it… gone?"

I gestured to my computer screen, still displaying the horrifying cascade of error messages. "Behold," I said dramatically, "the digital apocalypse."

Shira peered at the screen, her brow furrowed in concentration. She tapped a few keys on her laptop, connected to the synagogue's Wi-Fi (which, thanks to her tireless efforts, was surprisingly robust), and began to run diagnostics.

"Okay," she said after a moment, "it's definitely not good. Looks like… yeah, your Emacs initialization file is completely corrupted. The .emacs, gone to shmatta."

I winced. The .emacs file. My digital soul. The repository of years of painstakingly crafted customizations, keybindings, and mode configurations. The thought of it being corrupted was like… well, like finding out your favorite deli had run out of pastrami.

"So, what do we do?" I asked, my voice laced with anxiety. "Can it be salvaged? Can we… rebuild?"

Shira chewed on her lip, a habit I knew meant she was deep in thought. "Rebuilding is an option," she said slowly, "but it would take forever. You know how long it takes to get Emacs just right. It's like… like building the Temple in Jerusalem, but with more parentheses."

I nodded grimly. She was right. I had spent years tweaking and refining my Emacs configuration, adding custom packages, remapping keybindings, and generally bending the editor to my will. To start from scratch would be a monumental undertaking, a digital Sisyphean task.

Then, Shira's eyes widened, and a mischievous grin spread across her face. "But… there is another way," she said, her voice dropping to a conspiratorial whisper.

"Another way?" I asked, my heart leaping with hope. "What is it?"

She leaned in closer, as if sharing a sacred secret. "Have you ever heard," she said, "of the foobar mistsvah?"

I blinked. "The… the foobar mistsvah? Is that like a good deed with sample code?"

Shira rolled her eyes. "Not exactly, Rabbi Moe. It's more of a… legend. A myth. A whispered promise among the Emacs faithful."

"And what," I asked, my curiosity piqued, "is this legend?"

Shira took a deep breath. "The foobar mistsvah," she said, "is the ultimate Emacs configuration. A perfect, flawless setup that can solve any problem, overcome any obstacle, and generally make the world a better place, one keystroke at a time."

I raised an eyebrow. "That sounds… ambitious. Almost… messianic."

Shira shrugged. "Hey, we're talking about Emacs here. It's basically a religion already. But the thing is, the foobar mistsvah isn't just a configuration file. It's a… a state of mind. A way of approaching Emacs – and life – with the right combination of knowledge, skill, and chutzpah."

She paused, her eyes gleaming with fervor. "Legend has it that the foobar mistsvah can restore corrupted files, prevent buffer overflows, and even… unlock the secrets of the universe."

I stared at her, speechless. The foobar mistsvah? A perfect Emacs configuration that could solve any problem? It sounded too good to be true. Like a free lunch at a kosher deli.

"And you think," I said slowly, "that this… foobar mistsvah… can help me fix the synagogue's archive?"

Shira nodded enthusiastically. "I don't know for sure," she said, "but it's worth a shot. Besides, even if it doesn't work, the quest for the foobar mistsvah is a noble pursuit in itself. It's like… like searching for the lost Ark of the Covenant, but with more Lisp code."

I considered her words. The foobar mistsvah. It sounded like something out of a Borges story, a labyrinthine quest for an unattainable ideal. But the alternative – rebuilding my entire Emacs configuration from scratch – was even less appealing.

Besides, I had always been drawn to the esoteric and the mysterious. As a rabbi, I had spent years studying ancient texts and grappling with complex theological concepts. As an Emacs user, I had spent countless hours tweaking my configuration and exploring the hidden depths of the editor. The foobar mistsvah seemed like the perfect synthesis of my two passions, a chance to combine my religious and technological pursuits in a quest for ultimate enlightenment.

"Okay," I said, my voice filled with newfound determination. "I'm in. Let's find this foobar mistsvah."

Shira grinned, her blue hair practically vibrating with excitement. "Awesome!" she exclaimed. "But first," she added, glancing at her watch, "pizza. I'm starving."

As we ordered a large pepperoni (I know, I know, not kosher, but sometimes a rabbi needs a cheat day), I couldn't help but feel a sense of anticipation. The quest for the foobar mistsvah had begun. And I had a feeling it was going to be a wild ride.

But where to start? The internet, of course. Shira, while devouring a slice of pizza with the ferocity of a famished wolf, began to scour online Emacs communities, searching for any mention of the foobar mistsvah.

"There's a lot of… weird stuff out here," she said after a few minutes, her brow furrowed in concentration. "Conspiracy theories about Richard Stallman, debates about the best keybindings for kill-buffer, and… oh, wow, someone actually wrote an Emacs Lisp haiku about the foobar mistsvah."

I chuckled. "Only in the Emacs community," I said.

But as Shira delved deeper into the online rabbit hole, she began to uncover some more promising leads. She found references to a secret society of Emacs gurus, a group of Lisp masters who were said to possess the knowledge of the foobar mistsvah.

"They call themselves… the Order of the Init File," Shira said, her voice hushed with awe. "And they're supposed to meet in a secret location, once a year, to share their wisdom and discuss the future of Emacs."

"The Order of the Init File?" I repeated. "That sounds like something out of a Dan Brown novel. Do they wear robes and chant in Lisp?"

Shira shrugged. "I don't know," she said. "But I'm going to find out."

She typed furiously on her keyboard, following a trail of digital breadcrumbs that led her to a cryptic website, a forum hidden deep within the dark corners of the internet.

"I think I've found something," she said, her eyes widening. "A message board. For the Order of the Init File. And… it looks like they're planning a meeting. In Cambridge. Next week."

My heart skipped a beat. Cambridge. As in, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Home of MIT. The birthplace of Emacs.

Could it be? Were we about to stumble upon the secrets of the foobar mistsvah?

"Shira," I said, my voice trembling with excitement, "we have to go to Cambridge."

She grinned. "I was hoping you'd say that," she said. "I've always wanted to see MIT. Besides," she added, her eyes twinkling, "I hear they have amazing pizza."

And so, the pilgrimage began. The quest for the foobar mistsvah was taking us to the hallowed halls of MIT, to the heart of the Emacs universe.

But as we prepared for our journey, a nagging doubt crept into my mind. Was this all just a wild goose chase? A fool's errand? Or was there something more to the foobar mistsvah than just a legend?

Only time would tell. But one thing was certain: the fate of the synagogue's archive – and perhaps my sanity – depended on it.

As we packed our bags, I couldn't help but wonder what awaited us in Cambridge. Would we find the Order of the Init File? Would we unlock the secrets of the foobar mistsvah? And, most importantly, would we find decent kosher food?

The answers, I suspected, were waiting for us in the digital wilderness, hidden somewhere between the parentheses and the keybindings. And I, Rabbi Dr. Moishe "Moe" Perlstein, PhD (Emacs), was ready to face whatever challenges lay ahead.

Because, as any good Emacs user knows, the journey is just as important as the destination. And sometimes, the most profound truths are found not in ancient texts, but in the intricate, customizable depths of a well-configured Emacs buffer.

But the question remained, was the buffer a safe place or not?

The pizza, at least, was excellent. And the journey, I knew, was only just beginning.

Before we could embark on this quest for the foobar mistsvah, however, there was one rather large obstacle looming on the horizon.

Rabbi Lipschitz.

My nemesis, my foil, my… well, you get the idea. Rabbi Lipschitz, the staunch advocate of Vim, the self-proclaimed guardian of tradition, the bane of my Emacs-loving existence.

The thought of facing him, especially with the synagogue archive in such a state of disarray, filled me with dread. He would undoubtedly seize this opportunity to gloat, to preach the superiority of Vim, to generally make my life a living hell.

But I couldn't avoid him forever. He was, after all, a prominent member of the community, and he would undoubtedly be curious about the state of the archive.

I took a deep breath, steeled my nerves, and prepared for the inevitable confrontation.

Because, as any good rabbi knows, sometimes the greatest challenges come not from corrupted configuration files, but from stubborn colleagues.

And I had a feeling that Rabbi Lipschitz was about to become my biggest challenge yet.

The chapter ends.

The Prophecy of the Foobar Mistsvah

Chapter 3: The Vimite Heresy

Oy vey. If Mrs. Rosenblatt’s sigh was a heavy shtreimel, this… this was a whole fur store collapsing on my head. Just when I thought the day couldn't get any more… meshugge, Rabbi Lipschitz arrived. Lipschitz! The man whose very existence seemed to be a refutation of everything I held dear, both religiously and, dare I say it, editorially.

He swept into my study with the theatrical flair of a Broadway star announcing a matzah shortage. His tailored suit, a shade of gray that screamed “Upper West Side lawyer,” practically shimmered. His perfectly coiffed hair looked like it had been sculpted by Michelangelo himself (if Michelangelo had used hairspray, that is). And his smile… that smug, self-satisfied smile that could curdle milk.

“Moishe, Moishe, Moishe,” he clucked, shaking his head with mock sorrow. “Such a tragedy! The synagogue’s archive? Corrupted? And all because of… Emacs?” He practically spat the name out like a bad piece of gefilte fish.

Before I could muster a reply, he continued, his voice dripping with condescension. “I always said, Moishe, you’re too caught up in these… gadgets. These digital distractions. A rabbi should be focusing on the Torah, on the Talmud, not on… text editors!” He waved his hand dismissively, as if Emacs was some kind of frivolous toy.

“Ah, Lipschitz,” I sighed, rising to greet him, though every fiber of my being wanted to shove him into the nearest Lisp interpreter and debug him into oblivion. “Always a pleasure. And yes, a most unfortunate incident. But hardly the fault of Emacs. More likely… user error.” I said the last two words with a pointed glance, hoping he’d catch the subtle barb.

He chuckled, a low, rumbling sound that reminded me of a malfunctioning garbage disposal. “User error? Moishe, you wound me! Are you suggesting that you, Rabbi Dr. Moishe Perlstein, PhD (Emacs), are capable of making a mistake?” He feigned shock, placing a hand dramatically over his heart. “Perish the thought!”

“Nu, Lipschitz, even the greatest tzadik can stumble,” I said, invoking a little humility to mask my simmering irritation. “And besides, what brings you all the way to my humble abode? Surely you’re not just here to… schadenfreude?”

He adjusted his tie, a silk monstrosity that probably cost more than my entire computer setup. “Schadenfreude? Moishe, you do me an injustice! I came to offer my… assistance.” He paused for dramatic effect. “You see, I heard about your… predicament. And I thought, ‘What would a good neighbor do? He would offer a solution!’”

My eyebrows shot up. “A solution? From you? I’m all ears.” Though, frankly, I’d rather be deaf than listen to another one of his lectures on the superiority of Vim.

“Yes, Moishe, a solution so elegant, so efficient, so… vim-tastic!” He beamed, as if he’d just discovered the cure for baldness. “You see, I’ve been using Vim for decades. And in all that time, I’ve never encountered a problem that couldn’t be solved with a well-placed… command.”

I resisted the urge to roll my eyes. “And what command, pray tell, will restore my corrupted initialization file, Lipschitz? :recover? I think not.”

He wagged his finger at me. “Ah, Moishe, you’re so quick to dismiss! Vim is not just about commands, it’s about… philosophy! It’s about efficiency, about minimalism, about getting the job done with the least amount of… kvetching.”

Shira, who had been silently observing our little pas de deux, finally spoke up. “So, you’re saying Vim is like… a minimalist seder plate? Just the bare essentials?”

Lipschitz looked at her, momentarily flustered by her unexpected interruption. “Well, yes, in a way. It’s about focusing on the core principles, not getting bogged down in unnecessary… frills.”

“Like Emacs’s infinite customizability?” I interjected, unable to resist the jab.

“Exactly!” Lipschitz exclaimed, seizing the opportunity. “All those packages, all those modes, all those… distractions! It’s like trying to find the afikoman in a room full of dreidels!”

“And Vim is like… finding the afikoman with a single, perfectly crafted keystroke?” Shira quipped, her eyes twinkling.

Lipschitz puffed out his chest. “Precisely! It’s about… precision. About control. About being the master of your text editor, not the other way around.”

I sighed. “Lipschitz, with all due respect, this isn’t about philosophy, it’s about practicality. My archive is corrupted, and I need to fix it. Now, unless you have a magic Vim command that can undo the digital damage, I suggest you leave me to my… kvetching.”

He frowned. “But Moishe, I’m telling you, Vim is the answer! I could show you… I could convert your entire archive to Vim, and you’d never have these problems again!”

The thought of converting my entire archive to Vim sent a shiver down my spine. It was like suggesting I renounce my faith and convert to… well, to the digital equivalent of Reform Judaism.

“Lipschitz,” I said, my voice hardening, “I appreciate the offer, but I’m afraid I must decline. I am, and always will be, an Emacs man. It’s in my blood, it’s in my kishkes! Besides,” I added with a sly grin, “I’m pretty sure converting a synagogue archive to Vim would violate at least three different commandments.”

He scoffed. “Commandments? Moishe, you’re being ridiculous! This is about efficiency, about getting the job done! Are you going to let your religious dogma stand in the way of… progress?”

“Progress?” I retorted. “Or heresy, Lipschitz? The Vimite heresy, perhaps? Are you trying to start a new schism in the world of text editors? Are you trying to divide the faithful?”

He threw his hands up in the air. “Moishe, you’re impossible! I’m just trying to help!”

“And I appreciate that, Lipschitz. Truly. But I’m afraid your help is… unwanted. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I have a foobar mistsvah to pursue.”

Lipschitz stared at me, his face a mask of frustration. “A… foobar mistsvah? What in the world is that?”

I smiled mysteriously. “Ah, that, my friend, is a story for another time. Now, if you’ll excuse me…” I gestured towards the door.

He hesitated for a moment, then sighed again. “Fine, Moishe. But don’t say I didn’t warn you. You’re playing with fire. And Emacs, my friend, is a very flammable substance.” With that, he turned and stormed out of my study, leaving a faint scent of expensive cologne and a lingering sense of… dread.

Shira watched him go, then turned to me with a raised eyebrow. “Wow, Rabbi Moe, you really know how to handle the Vimites. That was… intense.”

“Intense is an understatement, Shira,” I said, sinking back into my chair. “That was a battle. A battle for the soul of my archive. A battle for the very future of Emacs. And, if I’m being honest, a battle that left me feeling… more confused than ever.”

“Confused? About what?” Shira asked.

“About everything, Shira! About Emacs, about Vim, about the foobar mistsvah, about whether I’m even qualified to be a rabbi in the age of digital disruption. About whether I should just give up and become a goat herder in the Catskills.”

Shira chuckled. “I don’t think goat herding is really your thing, Rabbi Moe. Besides, who would debug the synagogue’s Wi-Fi?”

I smiled weakly. “You’re right, Shira. I can’t abandon my flock. Even if they’re using carrier pigeons to communicate. But… this foobar mistsvah… I still don’t know what it is, or how to achieve it. All I know is that Lipschitz’s arrival has made me even more determined to find it. To prove that Emacs is not just a text editor, but a path to enlightenment. Or, at the very least, a way to fix a corrupted initialization file.”

“So, what’s the next step?” Shira asked, her eyes shining with anticipation.

I took a deep breath. “The next step, Shira, is to venture into the murky depths of the internet. To seek guidance from the online elders. To plumb the wisdom of the Emacs community. In short… we’re going to ask the nerds.” My stomach fluttered. “And I have a feeling,” I said, a chill running down my spine, “that what we find there will be even stranger than Rabbi Lipschitz’s love for Vim.”

The Vimite Smackdown

Ancient Arguments, Modern Editors

Chapter 4: The Wisdom of the Online Elders

Oy, the internet. A vast, swirling ocean of information, misinformation, cat videos, and… well, let’s just say things you wouldn’t show your bubbe. And yet, desperate times call for desperate measures. Shira, bless her teenage heart, had insisted that the answer to my corrupted init file lay not in some dusty tome or ancient rabbinical pronouncements, but in… the online Emacs community.

"Rabbi," she'd said, adjusting her headphones (currently pulsating with some sort of synthesized klezmer beat, I presumed), "the answer is out there. You just have to know where to look. Think of it as… digital tshuvah. Repenting for your sins against good coding practices by seeking forgiveness from the Emacs elders."

Forgiveness from the Emacs elders. The phrase conjured images of Gandalf-like figures hunched over glowing screens, dispensing wisdom in the form of cryptic Lisp functions. The reality, I suspected, would be slightly less… majestic.

Still, what choice did I have? Rabbi Lipschitz's smug pronouncements about Vim were still ringing in my ears, a constant, nagging reminder of my technological failings. I needed to find a solution, and Shira seemed to think that the online world was the key.

So, armed with a cup of lukewarm coffee and a healthy dose of skepticism, I ventured into the murky depths of the internet. Shira had pointed me towards several online forums, each with its own distinct flavor and cast of characters. There was "Emacs Stack Exchange," a surprisingly civil forum where users politely asked and answered questions about Emacs (mostly). Then there was "r/emacs," a Reddit community filled with memes, screenshots of customized Emacs setups, and the occasional flame war about the merits of various packages. And then there was… "GNU Emacs Help," a mailing list that seemed to be stuck in the 1990s, where questions were answered with terse, cryptic replies from users with names like "rms" and "xah_lee."

I decided to start with Emacs Stack Exchange, figuring it would be the least likely to result in a complete existential meltdown. I posted a detailed description of my problem, carefully explaining the symptoms, the potential causes, and the steps I had already taken to try to fix it. I even included a snippet of my (admittedly somewhat convoluted) init file.

Within minutes, I had several responses. One user suggested that I try restarting Emacs (duh!). Another suggested that I reinstall Emacs (slightly more helpful, but still not quite the breakthrough I was hoping for). And then there was a response from a user named "LispWizard666," who wrote:

"Sounds like a classic case of buffer bloat. Try clearing your minibuffer history and see if that helps. Also, make sure you're not using any deprecated functions. Those can cause all sorts of weirdness."

Buffer bloat? Deprecated functions? The terms swirled around in my head like gefilte fish in a blender. I had no idea what LispWizard666 was talking about, but his username was intriguing. Anyone who calls themselves LispWizard666 must know something about Emacs Lisp, right?

I replied to his comment, asking for more clarification. "Excuse me, LispWizard666," I wrote, "but I'm afraid I'm not familiar with the term 'buffer bloat.' Could you elaborate? And how would I go about identifying deprecated functions in my init file?"

His response was immediate and… unsettling. "Buffer bloat is when your minibuffer gets clogged with too much history. It's like a digital chazerai. As for deprecated functions, just grep your init file for 'defadvice' and replace them with 'advice-add'. Trust me, I'm a wizard."

Defadvice? Advice-add? Grep? My head was starting to spin. I felt like I was drowning in a sea of Lisp code, with no life raft in sight.

Shira, sensing my distress, peered over my shoulder. "Okay, Rabbi," she said, "this is getting a little too technical for you. Let me take over."

She sat down at the computer and started typing furiously, her fingers flying across the keyboard like a caffeinated hummingbird. Within minutes, she had cleared my minibuffer history, identified several deprecated functions in my init file, and replaced them with the modern equivalents.

"Okay," she said, leaning back in her chair, "try it now."

I held my breath and restarted Emacs. To my astonishment, the bug was gone! The synagogue's archive was no longer corrupted! The world was saved!

"Shira," I exclaimed, "you're a miracle worker! How did you do it?"

She shrugged. "It was just a few simple fixes. LispWizard666 gave us the right clues. We just had to know how to interpret them."

I looked back at LispWizard666's comment, suddenly filled with a newfound respect for the online Emacs community. These weren't just a bunch of nerds obsessing over a text editor; they were a community of knowledgeable and helpful individuals, willing to share their expertise with anyone who asked.

But who was LispWizard666? I couldn't shake the feeling that there was something… mysterious about him. His cryptic comments, his unsettling username, his uncanny ability to diagnose my problem from afar… it all seemed a little too… coincidental.

I decided to do some more research. I clicked on his profile and discovered that he had been a member of Emacs Stack Exchange for over ten years. He had answered thousands of questions, mostly about Emacs Lisp and advanced customization techniques. He had a reputation for being a brilliant but eccentric programmer, prone to disappearing for months at a time.

His profile also included a link to his personal website, a minimalist page with nothing but a single line of text: "The truth is out there… in the .emacs.d."

The .emacs.d. The sacred directory where all Emacs configurations are stored. Shira had mentioned something about it earlier, something about a hidden message. Could LispWizard666 be connected to this secret message? Could he be one of the Emacs gurus she had spoken of?

I clicked on the link to his .emacs.d directory, half expecting to find some sort of hidden code or encrypted message. Instead, I found… nothing. The directory was empty.

Or so it seemed.

As I stared at the empty directory, a sudden thought occurred to me. What if the message wasn't in the .emacs.d directory, but about it? What if the key to unlocking the "foobar mistsvah" lay not in some specific configuration, but in understanding the true nature of the .emacs.d itself?

Shira, overhearing my thoughts, chimed in. "Maybe we need to… git clone his .emacs.d? See the history, the commits, the… the evolution of his configuration?"

Git clone. Version control. Another layer of complexity added to this already convoluted quest. But Shira's idea had merit. Perhaps by examining the history of LispWizard666's .emacs.d, we could uncover the secrets of the "foobar mistsvah."

"Okay, Shira," I said, a newfound sense of determination filling my heart. "Let's clone this .emacs.d. Let's see what secrets it holds."

But as we prepared to delve deeper into the mysteries of LispWizard666 and his .emacs.d, I couldn't shake the feeling that we were about to stumble upon something far more profound than just a perfect Emacs configuration. We were about to confront the very nature of code, of faith, and of the strange and wondrous world that lies just beneath the surface of our digital lives. And maybe, just maybe, we were about to find the answer to the question that had been nagging at me ever since I first encountered that corrupted init file: What does it truly mean to be a Rabbi in the age of Emacs?

The Online Elders

Chapter 5: The Secret of the .Emacs.d

Nu, where were we? Ah, yes. Me, Rabbi Moe Perlstein, PhD (Emacs), staring into the digital abyss, or, more accurately, the slightly less dramatic but equally unsettling contents of my .emacs.d directory. Oy, .emacs.d, a folder that, to the uninitiated, looks like the digital equivalent of a hoarder's basement. But to an Emacs user, it's… well, it's still a hoarder's basement, but a carefully curated one, filled with treasures and potential time bombs in equal measure.

After Shira, may her fingers forever fly across the keyboard, worked her magic based on LispWizard666's cryptic pronouncements, the immediate crisis had subsided. The synagogue's archive was safe, Mrs. Rosenblatt was (relatively) happy, and Rabbi Lipschitz, that Vimite meshuggener, was temporarily silenced. But the experience left me with a lingering sense of unease. What was buffer bloat, really? And who was this LispWizard666, dispensing wisdom from the depths of the internet like some kind of digital Baal Shem Tov?

Shira, ever the pragmatist, shrugged. "He's probably just some guy with too much time on his hands," she said, already back to her synthesized klezmer beats. "Don't overthink it, Rabbi. Just be glad it's fixed."

But overthinking is what I do, Shira! It's practically a mitzvah in my book. (Or, at least, it would be if I could ever get around to writing that book. Maybe in Org mode, with a dedicated section for "Thoughts I've Overthought.")

So, I dove back into my .emacs.d directory, determined to unravel the mystery. It was a daunting task. My .emacs.d was a sprawling, chaotic mess, a testament to years of accumulated configurations, customizations, and half-baked ideas. It was a digital archaeological dig, revealing layers of my evolving relationship with Emacs, from my naive beginner days to my current state of slightly-less-naive-but-still-confused expert-ishness.

I started by examining the init.el file, the heart and soul of any Emacs configuration. It was a behemoth, a testament to my relentless pursuit of the perfect setup. I had sections for everything: syntax highlighting, auto-completion, spell checking, even a custom mode for writing Talmudic commentary (which, admittedly, I rarely used).

As I scrolled through the code, I noticed something… odd. Buried deep within a section dedicated to customizing the appearance of Org mode (because, of course, my notes needed to be beautiful), was a comment block that I didn't remember writing. It was written in plain English, but it felt… out of place, like a secret message hidden in plain sight.

The comment read:

;; Seek the Foobar Mistsvah.

;; The key lies within the ancient .emacs.d.

;; Follow the path to Cambridge, where the Lisp flows free.

;; MIT holds the secret. Beware the Vimites.

"Oy vey," I muttered to myself. "What in the name of Richard Stallman is this?"

The "Foobar Mistsvah" again! It was becoming an obsession, a digital dybbuk clinging to my init file. And what was this about an "ancient .emacs.d"? Was there some kind of… Emacs archaeology going on that I wasn't aware of?

And then there was the cryptic reference to Cambridge and MIT. Could it be? Was this a clue? A hint from some long-lost Emacs guru, guiding me towards the ultimate configuration?

My heart started to race. This was it! This was the breakthrough I'd been waiting for. The solution to my corrupted archive, the answer to my technological anxieties, the… well, maybe not the ultimate answer, but certainly a step in the right direction.

I immediately called Shira. "Shira! You won't believe this!" I exclaimed, practically shouting into the phone. "I found a secret message in my .emacs.d! It's about the Foobar Mistsvah! And MIT!"

Shira sighed. "Rabbi, did you get enough sleep last night? Maybe you're just hallucinating from too much Lisp code."

"No, no, I'm serious! It's right here, in the init.el! It says to go to Cambridge, to MIT! It says they hold the secret!"

There was a pause on the other end of the line. "Okay, Rabbi," Shira said slowly. "Let's just… back up for a second. You found a comment in your .emacs.d and you think it's a secret message leading you to MIT?"

"Well, yes! What else could it be?"

"Maybe it's just some random comment that someone added years ago and you forgot about it?"

"No, no, this feels different! It's… prophetic!" I declared, channeling my inner Isaiah.

Shira remained unconvinced, but she humored me. "Alright, Rabbi. Let's say, just for the sake of argument, that this is a secret message. What are you going to do? Just pack your bags and head to MIT?"

"Well, I… I hadn't thought that far ahead," I admitted.

"Of course not," Shira said with a sigh. "Look, Rabbi, I appreciate your enthusiasm, but you can't just go running off to Cambridge based on a cryptic comment in your .emacs.d. You have a synagogue to run, sermons to write, and Mrs. Rosenblatt to appease."

"But Shira, this could be the answer to everything! The Foobar Mistsvah! The perfect configuration! The… the end of buffer bloat!"

"Rabbi," Shira said firmly, "I'm going to give you some advice. Take a deep breath. Drink some tea. And then, maybe, do a little more research before you book a flight to Boston."

She hung up.

Oy. She had a point. I couldn't just abandon my responsibilities and chase after some mythical Emacs configuration. But the message… it felt so real, so urgent.

I decided to take Shira's advice, at least partially. I brewed myself a cup of chamomile tea (with a spoonful of honey, because even a rabbi needs a little sweetness in his life) and sat down at my computer. I started Googling.

"Foobar Mistsvah Emacs," I typed into the search bar. The results were… underwhelming. Mostly just links to obscure Emacs blogs and forum posts discussing the merits of various customization techniques. Nothing concrete, nothing that would confirm my suspicions about a secret society of Emacs gurus.

Then, I tried a different approach. "Ancient .emacs.d Cambridge MIT." This time, the results were more interesting. I found a few articles about the history of Emacs at MIT, mentioning the early days of Lisp programming and the legendary hackers who shaped the editor's development.

One article in particular caught my eye. It was a profile of a former MIT AI lab researcher named Ezra Klein (no relation to the Vox guy, as far as I could tell). Ezra was described as a brilliant but eccentric programmer who had disappeared from the public eye years ago. He was rumored to have been involved in some kind of secret project at MIT, something related to artificial intelligence and… well, you guessed it… Emacs.

The article mentioned that Ezra had been obsessed with the idea of creating a "perfect" Emacs configuration, a configuration so powerful and versatile that it could solve any problem. He called it… the "Foobar Mistsvah."

Oy vey! It was all coming together. The secret message, the reference to MIT, the Foobar Mistsvah… it was all connected. Ezra Klein was the key!

But where was he now? The article mentioned that he had dropped out of sight, living somewhere in seclusion. Nobody seemed to know his current whereabouts.

This was a problem. I needed to find Ezra Klein. He was the only one who could unlock the secret of the ancient .emacs.d and lead me to the Foobar Mistsvah.

I spent the rest of the evening scouring the internet, searching for any trace of Ezra Klein. I checked social media, online forums, even public records. But it was no use. He had vanished without a trace.

Just as I was about to give up, I stumbled upon a small, obscure blog dedicated to the history of the MIT AI lab. In the comments section of a post about early Lisp programming, I found a message from someone claiming to be a former colleague of Ezra Klein. The message was cryptic and vaguely paranoid, but it contained a single, tantalizing clue:

"If you're looking for Ezra, try the Cambridge Public Library. He used to spend hours there, poring over old books on Kabbalah and computer science. You might find him lurking in the stacks, muttering about the secrets of the universe."

The Cambridge Public Library. It wasn't much, but it was a lead. And in my quest for the Foobar Mistsvah, I would take any lead I could get.

I closed my laptop, feeling a surge of excitement and anticipation. The next day, I was going to Cambridge. I was going to find Ezra Klein. And I was going to unlock the secret of the ancient .emacs.d.

But as I drifted off to sleep, a nagging thought crept into my mind. The message in my .emacs.d had warned me to beware the Vimites. What if Rabbi Lipschitz, that meshuggener with his modal editing and his smug pronouncements, was somehow involved in all of this? What if he was trying to sabotage my quest for the Foobar Mistsvah?

Oy vey. This was going to be more complicated than I thought.

The Hidden Message

The Secret Society Symbol

Chapter 6: The Pilgrimage to Cambridge

Nu, Cambridge. Not the other Cambridge, the one with the scones and the rowing and the general air of British superiority. No, this was Cambridge, Massachusetts, the Athens of America, the home of Harvard, and, more importantly, the birthplace of Emacs itself. I felt like a chossid arriving in Lubavitch for Tishrei, only instead of a shtreimel, I was wearing my slightly-too-tight fedora, and instead of a kvitel (a prayer request), I was clutching a printout of LispWizard666's cryptic message.

The train ride from Penn Station was, let’s just say, an experience. Picture this: me, Rabbi Moe Perlstein, squeezed between a woman knitting what appeared to be a life-sized replica of a corgi and a college student blasting death metal through noise-canceling headphones that clearly weren't working. And all the while, I'm trying to decipher the meaning of "Follow the path to Cambridge, where the Lisp flows free." Was it literal? Did I need to find a river of Lisp? Should I bring waders? These were the questions that plagued me, oy, the questions that plagued me.

Finally, after what felt like an eternity (and several near-misses involving the corgi’s tail and my fedora), we arrived at South Station in Boston. From there, it was a quick ride on the T (the subway, for those not in the know) to Cambridge. As I emerged from the Kendall Square station, I felt a palpable shift in the atmosphere. It wasn't just the crisp New England air; it was the sheer density of intellectual energy. You could practically taste the algorithms, smell the theorems, and feel the collective brainpower vibrating in the air. It was… exhilarating. And slightly terrifying.

My first stop, naturally, was the MIT AI Lab. It was a pilgrimage, after all. I envisioned myself, a modern-day Maimonides, seeking enlightenment from the digital sages. The reality, as it often does, fell somewhat short of my expectations. The AI Lab wasn't some gleaming temple of technological innovation; it was a slightly run-down building with peeling paint and a distinct aroma of stale pizza and desperation.

I wandered through the hallways, feeling like a lost tourist in a foreign land. The walls were covered in posters advertising obscure lectures and cryptic diagrams that looked like they belonged in a geometry textbook from another dimension. I passed offices overflowing with empty soda cans, discarded circuit boards, and enough tangled wires to knit a small city.

The inhabitants of this digital wilderness were equally… eccentric. I encountered a professor with a beard that reached his knees, muttering about the halting problem while juggling oranges. A student with bright pink hair and more piercings than I thought humanly possible was debugging a neural network using a rubber duck. And then there was the guy wearing a t-shirt that read "There's no place like 127.0.0.1" who kept trying to sell me bitcoin.

"Excuse me," I said to a bewildered-looking student who was frantically typing at a keyboard. "Can you tell me where I might find… the secret society of Emacs gurus?"

He blinked at me, clearly not understanding a word I said. "Emacs? You mean like… the text editor?"

"Yes, yes! But more than that! A group of… enlightened individuals who have mastered the art of configuration! The keepers of the Foobar Mistsvah!" I exclaimed, perhaps a bit too enthusiastically.

The student took a step back, his eyes widening. "Dude," he said. "Are you okay? Maybe you should lay off the caffeine."

Defeated, I continued my wandering, feeling more lost than ever. The AI Lab was a labyrinth of intellectual pursuits, but I couldn't seem to find the path I was looking for. Everyone I encountered was either too busy, too confused, or too high on caffeine to understand my quest.

As I was about to give up hope, I stumbled upon a small, unassuming office tucked away in a corner of the building. The door was slightly ajar, and I could hear the faint sound of… Lisp code being executed? I peeked inside.

Seated at a desk piled high with books and papers was an elderly man with a kindly face and a mischievous twinkle in his eye. He was hunched over a computer, his fingers flying across the keyboard with a speed and precision that defied his age. The screen was filled with lines of Lisp code, interspersed with comments in a language I didn't recognize.

"Excuse me," I said, hesitantly. "Are you… by any chance… familiar with the Foobar Mistsvah?"

The man looked up, a slow smile spreading across his face. "Ah," he said, his voice raspy but warm. "So, the search continues. Come in, come in. You must be Rabbi Perlstein. I've been expecting you."

Oy vey. How did he know my name? Was this it? Was I finally on the right track?

He gestured to a chair across from his desk, which was precariously balanced on a stack of old computer manuals. "My name is Professor Abel," he said. "And I have a feeling you and I have much to discuss. But first," he added with a wink, "let's talk about keybindings."

The next few hours were a whirlwind of Lisp lectures, philosophical debates, and cryptic anecdotes. Professor Abel, it turned out, was a legendary figure in the Emacs community, one of the original hackers from the MIT AI Lab. He knew everything there was to know about Emacs, Lisp, and the history of the "Foobar Mistsvah."

He explained that the "Foobar Mistsvah" wasn't a single, perfect configuration, but a never-ending quest for improvement, a constant process of customization and refinement. It was about understanding the underlying principles of Emacs and adapting them to your own needs and preferences. It was, in essence, a metaphor for life itself.

He also revealed that the secret society of Emacs gurus was a real thing, though it was more of a loose-knit group of like-minded individuals than a formal organization. They met occasionally to share tips, debate techniques, and complain about the latest version of Emacs. But their primary goal was always the same: to push the boundaries of what was possible with the editor.

As the evening wore on, Professor Abel shared stories of the early days of Emacs, of the legendary "Emacs Wars" with the TECO editor, and of the philosophical debates that shaped the free software movement. He spoke with passion and conviction, his eyes gleaming with the fire of a true believer.

But then, his tone shifted. He became more somber, more reflective. He told me about the downsides of the Emacs obsession, of the hours lost to endless configuration, of the relationships strained by the pursuit of digital perfection. He warned me about the dangers of getting too caught up in the details, of losing sight of the bigger picture.

"Emacs is a powerful tool, Rabbi," he said. "But it's just a tool. It shouldn't consume your life. Don't let the code blind you to the world around you."

His words struck me like a thunderbolt. Was I becoming too obsessed with Emacs? Was I neglecting my duties as a rabbi in my pursuit of the "Foobar Mistsvah"? Was I… losing my way?

As I pondered these questions, Professor Abel handed me a small, tarnished key. "This," he said, "opens a door that has been closed for many years. It leads to a place where the secrets of Emacs are kept, a place where the Lisp truly flows free. But be warned, Rabbi. What you find there may not be what you expect."

He paused, his eyes filled with a mixture of hope and apprehension. "The key is yours now," he said. "Use it wisely."

I took the key, my hand trembling. What door did it open? What secrets did it hold? And what dangers awaited me on the other side?

"Where does this door lead?" I asked, my voice barely a whisper.

Professor Abel smiled enigmatically. "That, Rabbi," he said, "is for you to discover."

And with that, he turned back to his computer, his fingers already flying across the keyboard, lost once again in the world of Lisp.

I left Professor Abel's office feeling both exhilarated and terrified. I had found a clue, a key to unlocking the secrets of the "Foobar Mistsvah." But I also had a nagging feeling that I was about to open a Pandora's Box, a can of worms, a… well, you get the idea.

As I stepped out of the AI Lab and into the cool Cambridge night, I clutched the key in my hand, its cold metal a stark reminder of the task that lay ahead. I had a door to find, and a secret to uncover.

But first, I needed to find a good kosher deli. All this coding was making me hungry. And a rabbi can't solve the mysteries of the universe on an empty stomach, nu?

But as I walked away, I noticed someone watching me from across the street. A figure cloaked in shadows, their face obscured by a wide-brimmed hat. And in their hand, I could just make out the glint of… a Vim logo?

Oy vey. The Vimites were closing in. And I had a feeling that this pilgrimage was about to get a whole lot more complicated.

The Pilgrimage Begins

Chapter 7: The Confessions of the Lisp Hacker

Oy vey, Cambridge. I’d spent the better part of a day wandering those hallowed halls, dodging bewildered undergraduates and professors who looked like they’d accidentally wandered in from a parallel dimension. And now, finally, finally, I was sitting across from Professor Abel, a man who smelled faintly of old books and debugging sessions that had lasted far too long.

"So," I began, adjusting my fedora (which, by this point, was probably attracting its own ecosystem of dust mites). "You know about… the Foobar Mistsvah?"

Professor Abel chuckled, a dry, rustling sound like pages turning in an ancient volume. "Rabbi Perlstein," he said, "the Foobar Mistsvah is like the Riemann Hypothesis of the Emacs world. Everyone talks about it, some claim to have solved it, but no one truly understands it."

He leaned back in his chair, which creaked ominously. "You see, Rabbi, the Foobar Mistsvah isn't a thing, it's a process. It's the endless pursuit of the perfect configuration, the holy grail of Emacs customization. It's a never-ending quest."

"A never-ending quest?" I repeated, my heart sinking faster than a gefilte fish in a lead-lined bowl. "But… Shira said it could fix the bug!"

"Shira," Professor Abel said, a twinkle returning to his eye, "is a bright girl. But she, like many others, has fallen victim to the myth. The bug, Rabbi, is merely a symptom. The real problem lies deeper."

He paused, as if deciding whether to reveal a great secret. "It lies within the Society."

"The Society?" I perked up, my fedora nearly falling off in excitement. "The secret society of Emacs gurus? You were a member?"

"Once," Professor Abel said, his voice suddenly heavy with regret. "A long, long time ago. Back when Emacs was young, and we were… less burdened by reality."

He gestured to a cluttered corner of his office. "My name isn't really Abel, you know. It's Ezra. Ezra Kleinman. But that name… it carries too much baggage."

Ezra, formerly Abel, leaned forward, his eyes gleaming with a strange intensity. "We were a group of young, brilliant, utterly meshugge Lisp hackers. We believed we could build a better world, one Emacs package at a time. We called ourselves… the Lambda Cabal."

I nearly choked on my own saliva. "The Lambda… Cabal? That sounds like something out of a Dan Brown novel!"

Ezra shrugged. "We were young and dramatic. We thought we were unlocking the secrets of the universe with parentheses and cons cells. We met in secret, late at night, fueled by caffeine and the unwavering belief that we were on the verge of something… revolutionary."

He sighed, a long, drawn-out sound like a modem struggling to connect. "We were obsessed with the Foobar Mistsvah. We saw it as the ultimate expression of Emacs' power, a configuration so perfect it could solve any problem, predict the future, even… achieve enlightenment."

"Enlightenment?" I asked, my eyebrows reaching for the ceiling. "You thought Emacs could lead to enlightenment?"

"We thought," Ezra corrected, "that Emacs could be a tool for enlightenment. A way to structure our thoughts, to organize our lives, to connect with something larger than ourselves. We saw the act of customization as a form of meditation, a way of focusing our minds and achieving a state of flow."

"So, what happened?" I pressed. "Why did you leave the Lambda Cabal? Why did you abandon the quest for the Foobar Mistsvah?"

Ezra's face darkened. "We got… lost. Obsessed. We became so focused on the how that we forgot the why. We spent countless hours tweaking our configurations, writing elaborate Lisp functions, and arguing over the merits of different keybindings. We neglected our families, our friends, our real-world responsibilities. We became slaves to the machine."

He paused, his gaze fixed on some distant point in the past. "And then… the Great Divide."

"The Great Divide?" I prompted.

"A schism," Ezra explained. "A fundamental disagreement over the true nature of the Foobar Mistsvah. One faction, led by a particularly zealous hacker named… let's just call him 'The Macro Maven', believed that the Mistsvah could be achieved through sheer technical prowess, by writing the most complex and sophisticated code imaginable."

"And the other faction?" I asked.

"The other faction," Ezra said, his voice regaining a flicker of its former enthusiasm, "believed that the Mistsvah was about simplicity, about elegance, about understanding the underlying principles of Emacs and using them to create a configuration that was both powerful and intuitive."

"Which side were you on?" I asked, already knowing the answer.

"I was with the simplicity crowd," Ezra said, a hint of pride in his voice. "We believed that the true power of Emacs lay in its ability to adapt to the user, not the other way around. We saw the Macro Maven's approach as… well, as a digital Tower of Babel, a monument to ego and complexity that would ultimately collapse under its own weight."

The tension in the room was thicker than Mrs. Rosenblatt's brisket. I could practically feel the weight of Ezra's past, the burden of his disillusionment.

"The Great Divide led to… a fork," Ezra continued, his voice barely a whisper. "A permanent split in the Lambda Cabal. The Macro Maven and his followers went off to build their own version of the Foobar Mistsvah, a monstrous creation of tangled code and incomprehensible keybindings. We never heard from them again."

"And what happened to you?" I asked.

"I realized," Ezra said, "that the quest for the Foobar Mistsvah was a fool's errand. That there is no such thing as a perfect configuration, because perfection is an illusion. Emacs, like life, is messy, imperfect, and constantly evolving. The beauty lies not in achieving some unattainable ideal, but in the process of learning, growing, and adapting."

He looked at me, his eyes filled with a mixture of sadness and wisdom. "The true Foobar Mistsvah, Rabbi Perlstein, is not about finding the perfect configuration. It's about finding meaning in the act of configuring. It's about embracing the imperfection, the frustration, the occasional moments of triumph. It's about learning to love the process, even when it drives you crazy."

My mind reeled. This wasn't what I expected. I came to MIT expecting to find a magic bullet, a technological solution to my problems. Instead, I found a cautionary tale, a warning against the dangers of obsession and the futility of perfection.

"So," I said, feeling a bit deflated. "There's no way to fix the bug?"

Ezra smiled, a genuine, heartfelt smile that transformed his face. "Of course there is, Rabbi," he said. "But the solution isn't the Foobar Mistsvah. It's something much simpler."

He leaned closer, his voice dropping to a conspiratorial whisper. "It's… learning to read the error messages."

Oy vey. Of course. It was so obvious, so simple, so… Emacs.

Ezra spent the next few hours patiently guiding me through the intricacies of my corrupted init file, explaining the error messages, and helping me to identify the source of the bug. It was tedious work, but also strangely satisfying. As I slowly untangled the mess of code, I felt a sense of calm and focus that I hadn't experienced in years.

By the time I finally fixed the bug, the sun was beginning to rise. I felt exhausted, but also exhilarated. I had not achieved the Foobar Mistsvah, but I had learned something far more valuable: the importance of perseverance, the beauty of simplicity, and the power of human connection.

As I prepared to leave, Ezra placed a hand on my shoulder. "Remember, Rabbi," he said, "the quest for the Foobar Mistsvah never truly ends. There will always be new bugs to fix, new configurations to explore, new challenges to overcome. But as long as you approach the task with humility, curiosity, and a sense of humor, you will find meaning and purpose in the process."

He smiled again, a knowing smile that seemed to penetrate my very soul. "And one more thing, Rabbi," he added. "Back up your .emacs.d directory. Regularly."

Back in Brooklyn, the synagogue's archive was once again functioning perfectly. Shira, bless her heart, was ecstatic. Rabbi Lipschitz, however, remained skeptical.

"So," he said, his voice dripping with condescension. "You fixed the bug. Big deal. It still doesn't change the fact that Vim is a far superior editor."

I sighed. Some battles, it seemed, were never truly won. But as I looked at the familiar green text of my Emacs buffer, I felt a sense of peace and contentment. I had faced my demons, conquered my fears, and emerged stronger and wiser. And, perhaps more importantly, I had learned a valuable lesson about the true nature of the Foobar Mistsvah.

But... what about the Macro Maven? What dark corners of the internet was he lurking in, and would his monstrous creation ever rear its ugly head again? I shuddered, a new anxiety creeping into my thoughts.

As I closed my Emacs window for the night (after, of course, backing up my .emacs.d directory), I couldn't shake the feeling that my journey was far from over. The Foobar Mistsvah, like the Torah itself, was a never-ending story, a constant cycle of interpretation, adaptation, and renewal. And I, Rabbi Moe Perlstein, PhD (Emacs), was just beginning to write my chapter.

The Disillusioned Hacker

Chapter 8: The Ritual of Customization

Oy, customization. The very word conjures up images of late nights, bloodshot eyes, and enough parentheses to encircle the moon. But as Ezra, formerly Professor Abel, formerly a whole host of other identities I suspected, began to speak, I realized this wasn't just about tweaking a few settings. This was… well, it was still about tweaking settings, but with a kavanah, an intention, a something.

"Moe," Ezra began, his voice raspy like a rusty Lisp machine trying to boot up. "You think you want the Foobar Mistsvah. But the Mistsvah isn't something you get, it's something you become. It's like… like finally understanding the difference between let and let*. A subtle difference, but one that changes everything."

I blinked. "So… more parentheses?"

Ezra sighed, a sound that could curdle milk. "No, Moe. Less! The goal isn't to cram every feature and function into your .emacs.d. It's about understanding the principles. About knowing why you're doing something, not just how."

He gestured around his cluttered office, which looked like a digital dumpster fire. "Look at this mess! This isn't customization, this is hoarding. This is the .emacs.d of a man who's lost his way."

I couldn't help but feel a pang of recognition. My own .emacs.d wasn't quite this bad, but it was certainly trending in that direction. A sprawling, undocumented wilderness of custom functions and forgotten keybindings.

"So," I ventured, "where do we begin?"

Ezra stared at me for a long moment, his eyes piercing. "We begin with the init.el file, the heart of your Emacs configuration. It's like… like the ketubah, the marriage contract. It's the foundation upon which everything else is built. And yours, Moe, is a shanda."

He pulled up a terminal window and, with a few deft keystrokes, displayed my init.el file. It was… not pretty. A chaotic jumble of code, comments, and half-finished ideas.

"Oy vey," I muttered. "I haven't looked at that in months."

"Exactly!" Ezra exclaimed. "This isn't a living document, it's an archaeological dig! We need to clean this up, Moe. We need to refactor. We need to… we need to make it kosher."

And so began the ritual. Ezra, like a grizzled Mohel of the mainframe, guided me through the arcane process of Emacs customization. He showed me how to organize my code into logical sections, how to use comments to explain what each function did, and how to use packages to extend Emacs' functionality without cluttering up my init.el file.

"The key," Ezra explained, as he demonstrated the use of use-package, "is to be modular. Like the Mishnah! Each tractate, each chapter, self-contained, yet contributing to the whole. You want to be able to swap out packages without breaking everything."

He then launched into a lengthy discourse on the merits of different package managers – package.el, el-get, straight.el – each with its own quirks and advantages. It was like comparing different schools of Talmudic thought, each with its own interpretations and traditions.

"And," Ezra added, with a mischievous glint in his eye, "never trust a package that doesn't have a good README. It's like trusting a shadchan who can't produce any references!"

He then turned his attention to my keybindings, a subject that was near and dear to my heart. My keybindings were… eccentric, to say the least. A bizarre mix of Emacs defaults, custom shortcuts, and muscle memory quirks.

"Moe," Ezra said, his voice laced with a hint of pity, "these keybindings… they're a bubbe meise. A grandmother's tale! No rhyme, no reason, just a collection of random keystrokes."

He proceeded to dismantle my keybindings, one by one, explaining the logic behind each Emacs default and suggesting more efficient alternatives. It was a painful process, like having a dentist drill into my brain.

"Remember," Ezra said, as he remapped C-x C-s to C-s (a move that felt almost sacrilegious), "consistency is key. Like the laws of Shabbat! You can't just decide to invent your own rules. You need to follow the established traditions."

But then, he added, with a wink, "Unless, of course, you have a really good reason to deviate. Like… like if you need to save your file while simultaneously making a cup of coffee with your toes."

He then introduced me to the concept of "evil mode," a package that emulates Vim keybindings within Emacs.

"Now, I know what you're thinking," Ezra said, anticipating my horrified reaction. "Vim? The Amalekites of text editors? But hear me out, Moe. Evil mode isn't about abandoning Emacs, it's about embracing diversity. It's about understanding that there are different ways to achieve the same goal. It's like… like recognizing that there are different paths to God."

I was skeptical, to say the least. But Ezra insisted, and after a few hours of experimentation, I had to admit, there was something… compelling about evil mode. It was like discovering a hidden dimension within Emacs, a whole new way of interacting with the editor.

The days that followed were a blur of Lisp code, keybindings, and philosophical debates. Ezra, fueled by copious amounts of black coffee and a seemingly endless supply of granola bars, guided me through the intricacies of Emacs customization. He showed me how to write custom functions, how to create minor modes, and how to use hooks to extend Emacs' functionality.

He also taught me the importance of understanding the underlying principles of Emacs, the architecture, the data structures, the Lisp interpreter.

"Emacs," Ezra said, "isn't just a text editor, it's a Lisp machine disguised as a text editor. To truly master it, you need to understand the Lisp."

He then proceeded to give me a crash course in Emacs Lisp, explaining the concepts of lists, symbols, functions, and macros. It was like learning a new language, a language that was both elegant and maddeningly complex.

"Think of it like Kabbalah," Ezra said, his eyes gleaming with a strange intensity. "Each symbol, each function, a representation of a deeper reality. By mastering the Lisp, you're unlocking the secrets of the universe."

I wasn't sure about the universe part, but I had to admit, the more I learned about Emacs Lisp, the more I appreciated the power and flexibility of the editor. It was like having a magic wand, capable of transforming text, automating tasks, and even… solving bugs.

As I delved deeper into the world of Emacs customization, I began to see the Foobar Mistsvah in a new light. It wasn't about achieving perfection, it was about the process, the journey, the endless quest for knowledge and understanding.

It was about embracing the chaos, the complexity, the sheer meshugas of life, and using Emacs to make sense of it all.

And as I slowly, painstakingly, began to rebuild my init.el file, line by line, function by function, I felt a sense of… well, not enlightenment, exactly, but something close to it. A sense of purpose, a sense of connection, a sense that I was finally on the right path.

The bug in the synagogue's archive was still there, lurking in the shadows, waiting to strike again. But now, I felt ready to face it. Armed with my newfound knowledge of Emacs Lisp and my (slightly less chaotic) init.el file, I was confident that I could conquer any digital demon that dared to cross my path.

But then, just as I was about to declare victory, Ezra dropped a bombshell.

"There's one more thing, Moe," he said, his voice suddenly serious. "One more ritual you need to perform."

"What is it?" I asked, my heart sinking. "Another cryptic Lisp function? Another obscure keybinding?"

Ezra shook his head. "No. This is… different. This involves… artificial intelligence."

He paused, his eyes filled with a mixture of fear and fascination. "I've been working on a project, Moe. An AI that can… analyze Halakha. An AI that can… make rulings."

My jaw dropped. "An AI… making Halakha rulings? That's… that's heresy!"

Ezra shrugged. "Maybe. But it's also… the future. And I need your help, Moe. I need your expertise. I need your… rabbinical guidance."

He looked at me pleadingly. "Will you help me, Moe? Will you join me on this… this dangerous path?"

The question hung in the air, heavy with implications. I knew that if I agreed, I would be crossing a line, venturing into uncharted territory. But I also knew that I couldn't resist the temptation. The lure of the unknown, the challenge of the impossible, was too strong.

"Alright, Ezra," I said, my voice trembling slightly. "I'll help you. But if this AI starts spouting off about the permissibility of eating cheeseburgers on Yom Kippur, I'm pulling the plug."

Ezra smiled, a rare and precious sight. "Good," he said. "Then let's get started. Because the future of Halakha… is about to be rewritten."

The Ritual Begins

Learning Lisp

Chapter 9: The Temptation of AI Halakha

Oy, AI. Artificial Intelligence. The very words conjure up images of Skynet, sentient toasters demanding kashrut certification, and algorithms deciding who gets the last piece of cholent. It's enough to give a rabbi heartburn, even one who's spent more time wrestling with Lisp than lecturing on Leviticus.

After our deep dive into the customization rabbit hole, after Ezra had painstakingly (and painfully) pruned my keybindings and forced me to confront the existential dread of use-package, I felt… well, not enlightened, exactly. More like I’d survived a particularly intense Talmudic debate. My brain was buzzing with new commands, new concepts, and a renewed sense of purpose. The Foobar Mitzvah, that elusive perfect configuration, felt tantalizingly close, like a perfectly proofed challah dough just waiting to be baked.

And then, Ezra had to go and mention AI.

We were sitting in his office, surrounded by the usual chaos of wires, circuit boards, and empty coffee cups. I was basking in the afterglow of a successful git commit (a small victory, but in the world of Emacs, every little bit counts), when Ezra, apropos of nothing, said, "You know, Moe, there's a whole movement towards using AI in Halakha."

My ears perked up. "AI… in Halakha? You mean like… a robot rabbi?"

Ezra chuckled, a dry, rattling sound. "Not quite. More like AI systems that can analyze Jewish law, identify relevant precedents, and even offer… opinions."

"Opinions?" I sputtered. "Halakhic opinions from a computer? That's… that's meshugge! Halakha is about interpretation, about nuance, about the wisdom of generations! How can an algorithm possibly capture that?"

Ezra shrugged. "They claim it can. They feed it vast amounts of Talmudic text, responsa literature, and legal codes. The AI learns to identify patterns, connections, and contradictions. It can even generate arguments for different sides of a debate."

I felt a chill run down my spine. The idea was both fascinating and deeply unsettling. On the one hand, imagine the possibilities! An AI that could instantly access and analyze centuries of Jewish legal scholarship, providing rabbis with unparalleled resources for making informed decisions. On the other hand… imagine the dangers!